Reduced recompilations for workloads using temporary tables across multiple scopes

SQL Server 2019 introduces several performance optimizations which will improve performance with minimal changes required to your application code. In this blog post we’ll discuss one such improvement available in CTP 2.3: reduced recompilations for workloads using temporary tables in multiple scopes.

In order to understand this improvement, we’ll first go over the current behavior in SQL Server 2017 and prior. When referencing a temporary table with a DML statement (SELECT, INSERT, UPDATE, DELETE), if the temporary table was created by an outer scope batch, we will recompile the DML statement each time it is executed.

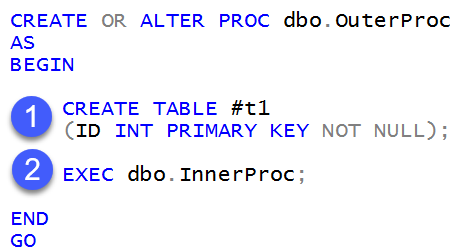

The following example illustrates this behavior:

In the outer procedure we:

- Create a temporary table

- Call a stored procedure

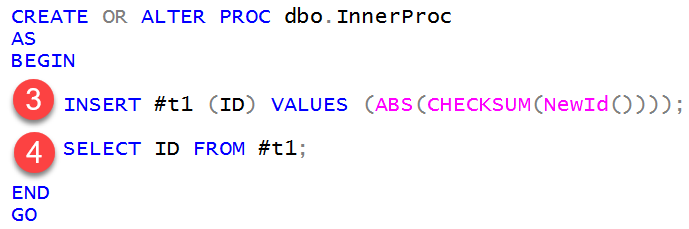

The inner stored procedure definition is as follows:

For the inner stored procedure, we have two DML statements that reference the temporary table created in the outer scope where we:

- Insert a row into the temporary table.

- Return the row from the temporary table.

We created the temporary table in a different scope from the DML statements, and for the existing implementation (pre-SQL Server 2019), we don’t “trust” that this temporary table schema hasn’t been materially changed and so we recompile the associated DML statements each time they are executed. This additional recompilation activity increases CPU utilization and can decrease overall workload performance and throughput.

Starting with SQL Server 2019 CTP 2.3, we will perform additional lightweight checks to avoid unnecessary recompilations:

- We will check if the outer-scope module used for creating the temporary table at compile time is the same one used for consecutive executions.

- We will keep track of any data definition language (DDL) changes made at initial compilation and compare them with DDL operations for consecutive executions.

The end result is a reduction in unwarranted recompilations and associated CPU-overhead.

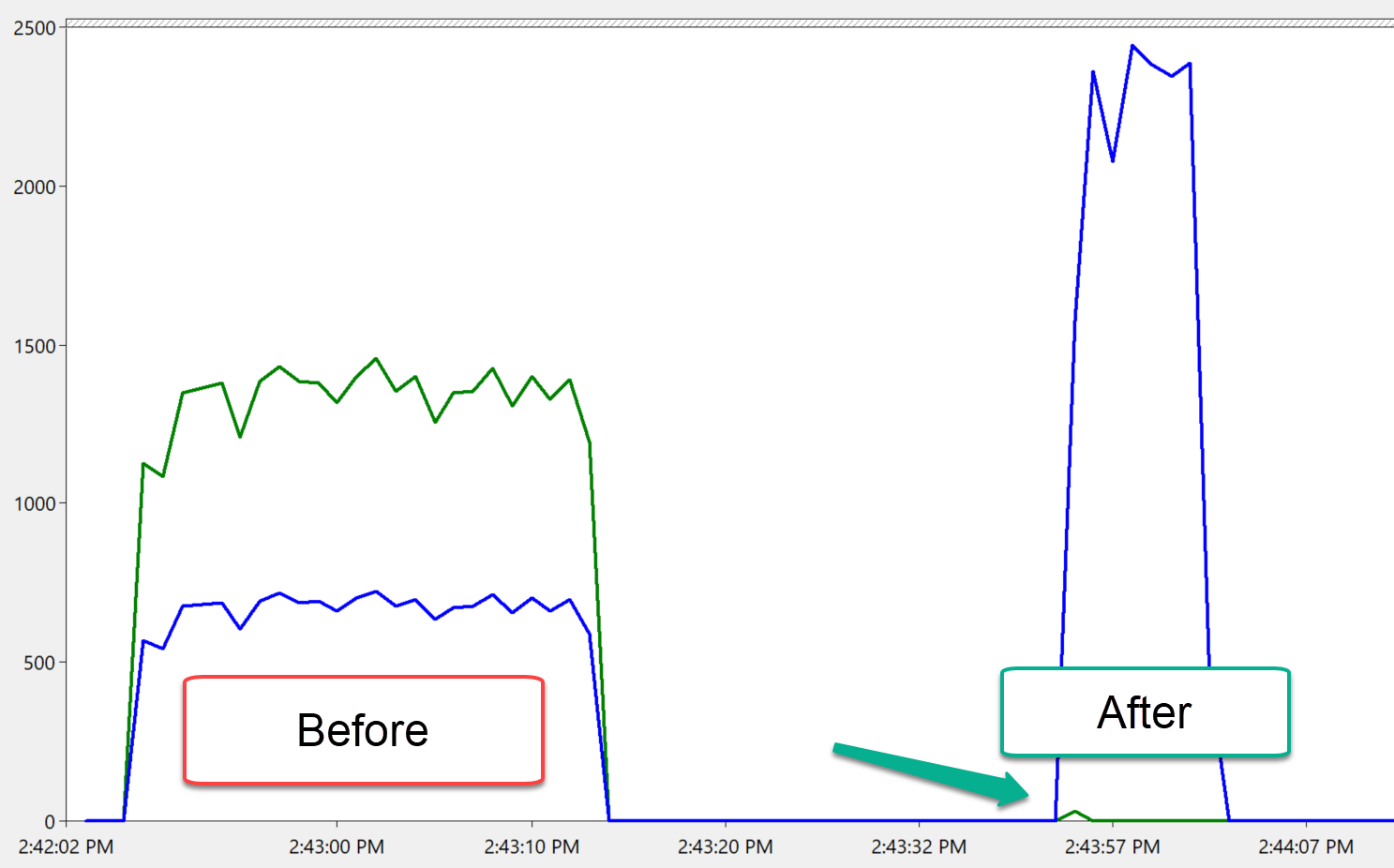

The below figure shows test results from 16 concurrent threads each executing the “OutProc” stored procedure 1,000 times (in a loop). The Y-axis represents the number of occurrences, with the blue line representing Batch Requests/sec and the green line representing SQL Re-Compilations/sec:

When the feature was enabled, for this example we saw:

- Improved throughput, as represented by Batch Requests/sec (blue line, second hump).

- Shorter overall workload duration.

- Reduced recompilations, as represented by SQL Re-Compilations/sec (green line) showing only a small increase at the beginning of the second test.

This feature is enabled by default in SQL Server 2019 CTP 2.3 under all database compatibility levels. As of this writing, this feature is also enabled in Azure SQL Database under database compatibility level 150, although it will soon be applied across all database compatibility levels (matching the behavior of SQL Server 2019).

If you have feedback on this feature or other query processing features, please email us at IntelligentQP@microsoft.com.

Comments

- Anonymous

March 05, 2019

Who on earth does that? Why would you need to do that? I didn't even know you could!Someone inspecting dbo.InnerProc in isolation will rightly wonder where on earth this #t1 has come from.A most peculiar design pattern that I would be loath to encourage.- Anonymous

March 05, 2019

Hi Kevnotec,We found that this was a * very * common pattern (creating a temporary table in one scope, populating it in another). - Anonymous

March 05, 2019

@Kevnotec We are completely guilty as charged here! (Though not with procedures that get invoked hundreds of times per second.)Developers who were used to modular internal code that can be reused by multiple procedures found this pattern to be a convenient way of benefiting from the optimizations in tempdb and easily passing a large rowset between procedures (e.g., to an internal "helper" procedure that either explicitly by permissions or implicitly by naming convention is not exposed publicly).That's not to say it's ideal or the best pattern, but it's worked for us for internal (not invoked directly by the application) procedures without any trouble, so we're in no rush to "fix" code that has worked fine for a decade :) - Anonymous

March 05, 2019

Hi Kevnotec,Regarding your comment "Someone inspecting dbo.InnerProc in isolation will rightly wonder where on earth this #t1 has come from", I would say that this is why all code should be commented. In this case, I would include what the temp table definition is in the comments, and the procedures / processes that create it and then call this procedure. - Anonymous

March 05, 2019

I've employed this technique a lot over the years, and will have to continue to so until Microsoft gets it act together and make table-valued parameters read-write (for calls between stored procedures, not calls from the client).There are a couple of way to this, and temp tables is one of them. I cover these methods in my article How to Share Data between Stored Procedures on http://www.sommarskog.se/share_data.html. Which I will need to update because of this change!

- Anonymous

- Anonymous

March 05, 2019

I would like to have the ability to set the statistics for a temp table (in one or more specific procedures, in case different temp tables of the same name is used in more than one place). This could be done in any number ways, example, create and populate the temp table, create/update index/column statistics. then tell SQL to apply it for certain procedures. Or I could have permanent tables that are populated, create/update statistics, then associate it with specific temp tables in specified procedures. So when that temp table is created, it automatically gets the statistics from the associated normal table (but not the data).The primary purpose is to avoid the 6 rows modified recompile, (potentially the 500 row recompile as well).This could also be applied to table variables.