Domain events: Design and implementation

Tip

This content is an excerpt from the eBook, .NET Microservices Architecture for Containerized .NET Applications, available on .NET Docs or as a free downloadable PDF that can be read offline.

Use domain events to explicitly implement side effects of changes within your domain. In other words, and using DDD terminology, use domain events to explicitly implement side effects across multiple aggregates. Optionally, for better scalability and less impact in database locks, use eventual consistency between aggregates within the same domain.

What is a domain event?

An event is something that has happened in the past. A domain event is, something that happened in the domain that you want other parts of the same domain (in-process) to be aware of. The notified parts usually react somehow to the events.

An important benefit of domain events is that side effects can be expressed explicitly.

For example, if you're just using Entity Framework and there has to be a reaction to some event, you would probably code whatever you need close to what triggers the event. So the rule gets coupled, implicitly, to the code, and you have to look into the code to, hopefully, realize the rule is implemented there.

On the other hand, using domain events makes the concept explicit, because there's a DomainEvent and at least one DomainEventHandler involved.

For example, in the eShop application, when an order is created, the user becomes a buyer, so an OrderStartedDomainEvent is raised and handled in the ValidateOrAddBuyerAggregateWhenOrderStartedDomainEventHandler, so the underlying concept is evident.

In short, domain events help you to express, explicitly, the domain rules, based in the ubiquitous language provided by the domain experts. Domain events also enable a better separation of concerns among classes within the same domain.

It's important to ensure that, just like a database transaction, either all the operations related to a domain event finish successfully or none of them do.

Domain events are similar to messaging-style events, with one important difference. With real messaging, message queuing, message brokers, or a service bus using AMQP, a message is always sent asynchronously and communicated across processes and machines. This is useful for integrating multiple Bounded Contexts, microservices, or even different applications. However, with domain events, you want to raise an event from the domain operation you're currently running, but you want any side effects to occur within the same domain.

The domain events and their side effects (the actions triggered afterwards that are managed by event handlers) should occur almost immediately, usually in-process, and within the same domain. Thus, domain events could be synchronous or asynchronous. Integration events, however, should always be asynchronous.

Domain events versus integration events

Semantically, domain and integration events are the same thing: notifications about something that just happened. However, their implementation must be different. Domain events are just messages pushed to a domain event dispatcher, which could be implemented as an in-memory mediator based on an IoC container or any other method.

On the other hand, the purpose of integration events is to propagate committed transactions and updates to additional subsystems, whether they are other microservices, Bounded Contexts or even external applications. Hence, they should occur only if the entity is successfully persisted, otherwise it's as if the entire operation never happened.

As mentioned before, integration events must be based on asynchronous communication between multiple microservices (other Bounded Contexts) or even external systems/applications.

Thus, the event bus interface needs some infrastructure that allows inter-process and distributed communication between potentially remote services. It can be based on a commercial service bus, queues, a shared database used as a mailbox, or any other distributed and ideally push based messaging system.

Domain events as a preferred way to trigger side effects across multiple aggregates within the same domain

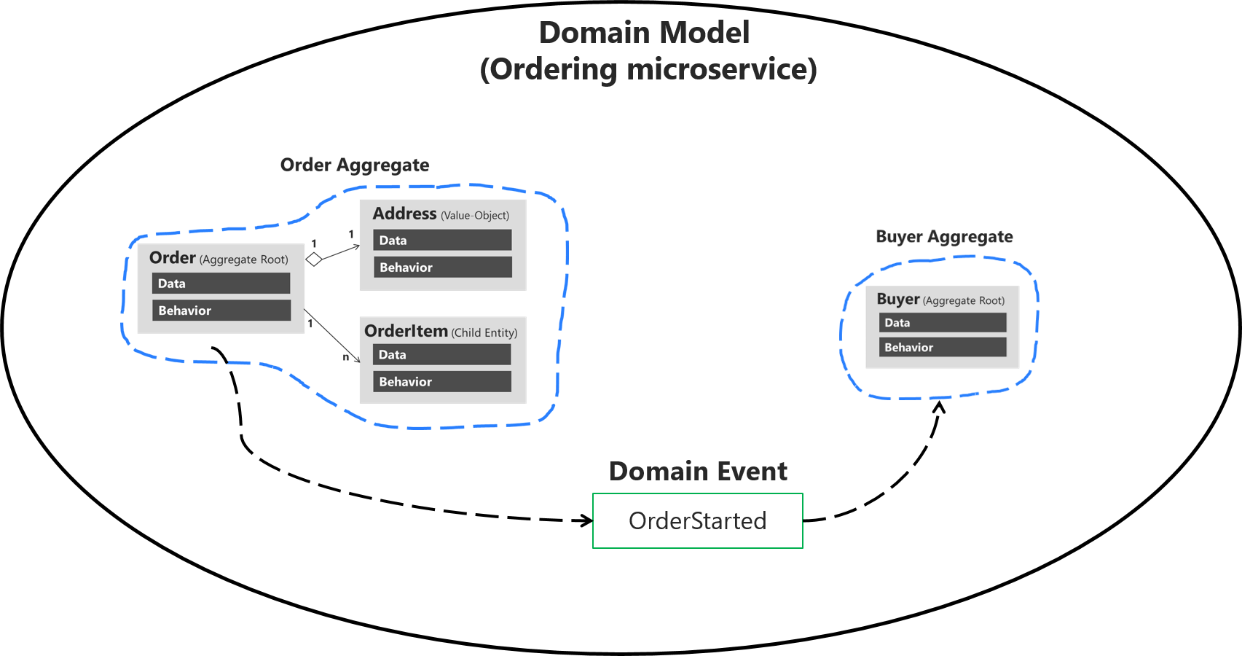

If executing a command related to one aggregate instance requires additional domain rules to be run on one or more additional aggregates, you should design and implement those side effects to be triggered by domain events. As shown in Figure 7-14, and as one of the most important use cases, a domain event should be used to propagate state changes across multiple aggregates within the same domain model.

Figure 7-14. Domain events to enforce consistency between multiple aggregates within the same domain

Figure 7-14 shows how consistency between aggregates is achieved by domain events. When the user initiates an order, the Order Aggregate sends an OrderStarted domain event. The OrderStarted domain event is handled by the Buyer Aggregate to create a Buyer object in the ordering microservice, based on the original user info from the identity microservice (with information provided in the CreateOrder command).

Alternately, you can have the aggregate root subscribed for events raised by members of its aggregates (child entities). For instance, each OrderItem child entity can raise an event when the item price is higher than a specific amount, or when the product item amount is too high. The aggregate root can then receive those events and perform a global calculation or aggregation.

It's important to understand that this event-based communication is not implemented directly within the aggregates; you need to implement domain event handlers.

Handling the domain events is an application concern. The domain model layer should only focus on the domain logic—things that a domain expert would understand, not application infrastructure like handlers and side-effect persistence actions using repositories. Therefore, the application layer level is where you should have domain event handlers triggering actions when a domain event is raised.

Domain events can also be used to trigger any number of application actions, and what is more important, must be open to increase that number in the future in a decoupled way. For instance, when the order is started, you might want to publish a domain event to propagate that info to other aggregates or even to raise application actions like notifications.

The key point is the open number of actions to be executed when a domain event occurs. Eventually, the actions and rules in the domain and application will grow. The complexity or number of side-effect actions when something happens will grow, but if your code were coupled with "glue" (that is, creating specific objects with new), then every time you needed to add a new action you would also need to change working and tested code.

This change could result in new bugs and this approach also goes against the Open/Closed principle from SOLID. Not only that, the original class that was orchestrating the operations would grow and grow, which goes against the Single Responsibility Principle (SRP).

On the other hand, if you use domain events, you can create a fine-grained and decoupled implementation by segregating responsibilities using this approach:

- Send a command (for example, CreateOrder).

- Receive the command in a command handler.

- Execute a single aggregate's transaction.

- (Optional) Raise domain events for side effects (for example, OrderStartedDomainEvent).

- Handle domain events (within the current process) that will execute an open number of side effects in multiple aggregates or application actions. For example:

- Verify or create buyer and payment method.

- Create and send a related integration event to the event bus to propagate states across microservices or trigger external actions like sending an email to the buyer.

- Handle other side effects.

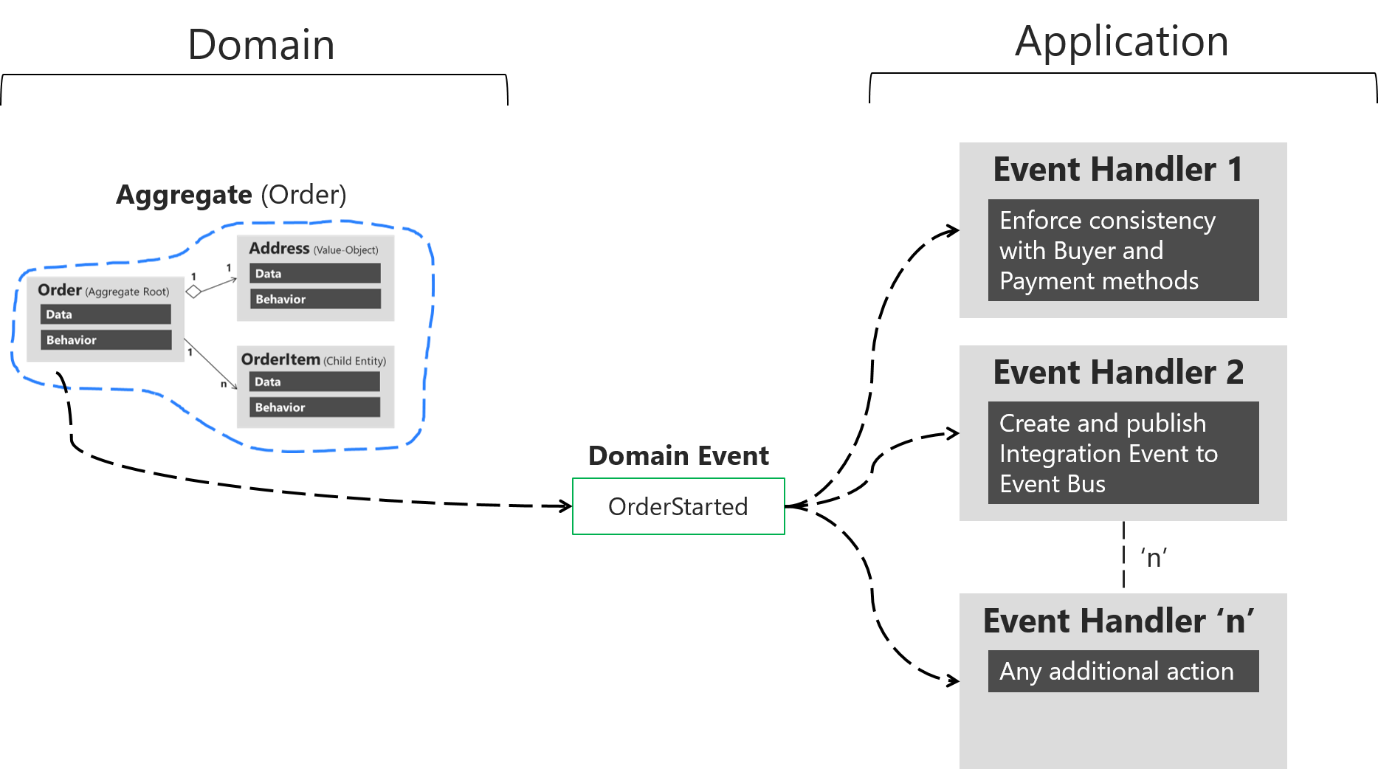

As shown in Figure 7-15, starting from the same domain event, you can handle multiple actions related to other aggregates in the domain or additional application actions you need to perform across microservices connecting with integration events and the event bus.

Figure 7-15. Handling multiple actions per domain

There can be several handlers for the same domain event in the Application Layer, one handler can solve consistency between aggregates and another handler can publish an integration event, so other microservices can do something with it. The event handlers are typically in the application layer, because you'll use infrastructure objects like repositories or an application API for the microservice's behavior. In that sense, event handlers are similar to command handlers, so both are part of the application layer. The important difference is that a command should be processed only once. A domain event could be processed zero or n times, because it can be received by multiple receivers or event handlers with a different purpose for each handler.

Having an open number of handlers per domain event allows you to add as many domain rules as needed, without affecting current code. For instance, implementing the following business rule might be as easy as adding a few event handlers (or even just one):

When the total amount purchased by a customer in the store, across any number of orders, exceeds $6,000, apply a 10% off discount to every new order and notify the customer with an email about that discount for future orders.

Implement domain events

In C#, a domain event is simply a data-holding structure or class, like a DTO, with all the information related to what just happened in the domain, as shown in the following example:

public class OrderStartedDomainEvent : INotification

{

public string UserId { get; }

public string UserName { get; }

public int CardTypeId { get; }

public string CardNumber { get; }

public string CardSecurityNumber { get; }

public string CardHolderName { get; }

public DateTime CardExpiration { get; }

public Order Order { get; }

public OrderStartedDomainEvent(Order order, string userId, string userName,

int cardTypeId, string cardNumber,

string cardSecurityNumber, string cardHolderName,

DateTime cardExpiration)

{

Order = order;

UserId = userId;

UserName = userName;

CardTypeId = cardTypeId;

CardNumber = cardNumber;

CardSecurityNumber = cardSecurityNumber;

CardHolderName = cardHolderName;

CardExpiration = cardExpiration;

}

}

This is essentially a class that holds all the data related to the OrderStarted event.

In terms of the ubiquitous language of the domain, since an event is something that happened in the past, the class name of the event should be represented as a past-tense verb, like OrderStartedDomainEvent or OrderShippedDomainEvent. That's how the domain event is implemented in the ordering microservice in eShop.

As noted earlier, an important characteristic of events is that since an event is something that happened in the past, it shouldn't change. Therefore, it must be an immutable class. You can see in the previous code that the properties are read-only. There's no way to update the object, you can only set values when you create it.

It's important to highlight here that if domain events were to be handled asynchronously, using a queue that required serializing and deserializing the event objects, the properties would have to be "private set" instead of read-only, so the deserializer would be able to assign the values upon dequeuing. This is not an issue in the Ordering microservice, as the domain event pub/sub is implemented synchronously using MediatR.

Raise domain events

The next question is how to raise a domain event so it reaches its related event handlers. You can use multiple approaches.

Udi Dahan originally proposed (for example, in several related posts, such as Domain Events – Take 2) using a static class for managing and raising the events. This might include a static class named DomainEvents that would raise domain events immediately when it's called, using syntax like DomainEvents.Raise(Event myEvent). Jimmy Bogard wrote a blog post (Strengthening your domain: Domain Events) that recommends a similar approach.

However, when the domain events class is static, it also dispatches to handlers immediately. This makes testing and debugging more difficult, because the event handlers with side-effects logic are executed immediately after the event is raised. When you're testing and debugging, you just want to focus on what is happening in the current aggregate classes; you don't want to suddenly be redirected to other event handlers for side effects related to other aggregates or application logic. This is why other approaches have evolved, as explained in the next section.

The deferred approach to raise and dispatch events

Instead of dispatching to a domain event handler immediately, a better approach is to add the domain events to a collection and then to dispatch those domain events right before or right after committing the transaction (as with SaveChanges in EF). (This approach was described by Jimmy Bogard in this post A better domain events pattern.)

Deciding if you send the domain events right before or right after committing the transaction is important, since it determines whether you will include the side effects as part of the same transaction or in different transactions. In the latter case, you need to deal with eventual consistency across multiple aggregates. This topic is discussed in the next section.

The deferred approach is what eShop uses. First, you add the events happening in your entities into a collection or list of events per entity. That list should be part of the entity object, or even better, part of your base entity class, as shown in the following example of the Entity base class:

public abstract class Entity

{

//...

private List<INotification> _domainEvents;

public List<INotification> DomainEvents => _domainEvents;

public void AddDomainEvent(INotification eventItem)

{

_domainEvents = _domainEvents ?? new List<INotification>();

_domainEvents.Add(eventItem);

}

public void RemoveDomainEvent(INotification eventItem)

{

_domainEvents?.Remove(eventItem);

}

//... Additional code

}

When you want to raise an event, you just add it to the event collection from code at any method of the aggregate-root entity.

The following code, part of the Order aggregate-root at eShop, shows an example:

var orderStartedDomainEvent = new OrderStartedDomainEvent(this, //Order object

cardTypeId, cardNumber,

cardSecurityNumber,

cardHolderName,

cardExpiration);

this.AddDomainEvent(orderStartedDomainEvent);

Notice that the only thing that the AddDomainEvent method is doing is adding an event to the list. No event is dispatched yet, and no event handler is invoked yet.

You actually want to dispatch the events later on, when you commit the transaction to the database. If you are using Entity Framework Core, that means in the SaveChanges method of your EF DbContext, as in the following code:

// EF Core DbContext

public class OrderingContext : DbContext, IUnitOfWork

{

// ...

public async Task<bool> SaveEntitiesAsync(CancellationToken cancellationToken = default(CancellationToken))

{

// Dispatch Domain Events collection.

// Choices:

// A) Right BEFORE committing data (EF SaveChanges) into the DB. This makes

// a single transaction including side effects from the domain event

// handlers that are using the same DbContext with Scope lifetime

// B) Right AFTER committing data (EF SaveChanges) into the DB. This makes

// multiple transactions. You will need to handle eventual consistency and

// compensatory actions in case of failures.

await _mediator.DispatchDomainEventsAsync(this);

// After this line runs, all the changes (from the Command Handler and Domain

// event handlers) performed through the DbContext will be committed

var result = await base.SaveChangesAsync();

}

}

With this code, you dispatch the entity events to their respective event handlers.

The overall result is that you've decoupled the raising of a domain event (a simple add into a list in memory) from dispatching it to an event handler. In addition, depending on what kind of dispatcher you are using, you could dispatch the events synchronously or asynchronously.

Be aware that transactional boundaries come into significant play here. If your unit of work and transaction can span more than one aggregate (as when using EF Core and a relational database), this can work well. But if the transaction cannot span aggregates, you have to implement additional steps to achieve consistency. This is another reason why persistence ignorance is not universal; it depends on the storage system you use.

Single transaction across aggregates versus eventual consistency across aggregates

The question of whether to perform a single transaction across aggregates versus relying on eventual consistency across those aggregates is a controversial one. Many DDD authors like Eric Evans and Vaughn Vernon advocate the rule that one transaction = one aggregate and therefore argue for eventual consistency across aggregates. For example, in his book Domain-Driven Design, Eric Evans says this:

Any rule that spans Aggregates will not be expected to be up-to-date at all times. Through event processing, batch processing, or other update mechanisms, other dependencies can be resolved within some specific time. (page 128)

Vaughn Vernon says the following in Effective Aggregate Design. Part II: Making Aggregates Work Together:

Thus, if executing a command on one aggregate instance requires that additional business rules execute on one or more aggregates, use eventual consistency [...] There is a practical way to support eventual consistency in a DDD model. An aggregate method publishes a domain event that is in time delivered to one or more asynchronous subscribers.

This rationale is based on embracing fine-grained transactions instead of transactions spanning many aggregates or entities. The idea is that in the second case, the number of database locks will be substantial in large-scale applications with high scalability needs. Embracing the fact that highly scalable applications need not have instant transactional consistency between multiple aggregates helps with accepting the concept of eventual consistency. Atomic changes are often not needed by the business, and it is in any case the responsibility of the domain experts to say whether particular operations need atomic transactions or not. If an operation always needs an atomic transaction between multiple aggregates, you might ask whether your aggregate should be larger or wasn't correctly designed.

However, other developers and architects like Jimmy Bogard are okay with spanning a single transaction across several aggregates—but only when those additional aggregates are related to side effects for the same original command. For instance, in A better domain events pattern, Bogard says this:

Typically, I want the side effects of a domain event to occur within the same logical transaction, but not necessarily in the same scope of raising the domain event [...] Just before we commit our transaction, we dispatch our events to their respective handlers.

If you dispatch the domain events right before committing the original transaction, it is because you want the side effects of those events to be included in the same transaction. For example, if the EF DbContext SaveChanges method fails, the transaction will roll back all changes, including the result of any side effect operations implemented by the related domain event handlers. This is because the DbContext life scope is by default defined as "scoped." Therefore, the DbContext object is shared across multiple repository objects being instantiated within the same scope or object graph. This coincides with the HttpRequest scope when developing Web API or MVC apps.

Actually, both approaches (single atomic transaction and eventual consistency) can be right. It really depends on your domain or business requirements and what the domain experts tell you. It also depends on how scalable you need the service to be (more granular transactions have less impact with regard to database locks). And it depends on how much investment you're willing to make in your code, since eventual consistency requires more complex code in order to detect possible inconsistencies across aggregates and the need to implement compensatory actions. Consider that if you commit changes to the original aggregate and afterwards, when the events are being dispatched, if there's an issue and the event handlers cannot commit their side effects, you'll have inconsistencies between aggregates.

A way to allow compensatory actions would be to store the domain events in additional database tables so they can be part of the original transaction. Afterwards, you could have a batch process that detects inconsistencies and runs compensatory actions by comparing the list of events with the current state of the aggregates. The compensatory actions are part of a complex topic that will require deep analysis from your side, which includes discussing it with the business user and domain experts.

In any case, you can choose the approach you need. But the initial deferred approach—raising the events before committing, so you use a single transaction—is the simplest approach when using EF Core and a relational database. It's easier to implement and valid in many business cases. It's also the approach used in the ordering microservice in eShop.

But how do you actually dispatch those events to their respective event handlers? What's the _mediator object you see in the previous example? It has to do with the techniques and artifacts you use to map between events and their event handlers.

The domain event dispatcher: mapping from events to event handlers

Once you're able to dispatch or publish the events, you need some kind of artifact that will publish the event, so that every related handler can get it and process side effects based on that event.

One approach is a real messaging system or even an event bus, possibly based on a service bus as opposed to in-memory events. However, for the first case, real messaging would be overkill for processing domain events, since you just need to process those events within the same process (that is, within the same domain and application layer).

How to subscribe to domain events

When you use MediatR, each event handler must use an event type that is provided on the generic parameter of the INotificationHandler interface, as you can see in the following code:

public class ValidateOrAddBuyerAggregateWhenOrderStartedDomainEventHandler

: INotificationHandler<OrderStartedDomainEvent>

Based on the relationship between event and event handler, which can be considered the subscription, the MediatR artifact can discover all the event handlers for each event and trigger each one of those event handlers.

How to handle domain events

Finally, the event handler usually implements application layer code that uses infrastructure repositories to obtain the required additional aggregates and to execute side-effect domain logic. The following domain event handler code at eShop, shows an implementation example.

public class ValidateOrAddBuyerAggregateWhenOrderStartedDomainEventHandler

: INotificationHandler<OrderStartedDomainEvent>

{

private readonly ILogger _logger;

private readonly IBuyerRepository _buyerRepository;

private readonly IOrderingIntegrationEventService _orderingIntegrationEventService;

public ValidateOrAddBuyerAggregateWhenOrderStartedDomainEventHandler(

ILogger<ValidateOrAddBuyerAggregateWhenOrderStartedDomainEventHandler> logger,

IBuyerRepository buyerRepository,

IOrderingIntegrationEventService orderingIntegrationEventService)

{

_buyerRepository = buyerRepository ?? throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(buyerRepository));

_orderingIntegrationEventService = orderingIntegrationEventService ?? throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(orderingIntegrationEventService));

_logger = logger ?? throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(logger));

}

public async Task Handle(

OrderStartedDomainEvent domainEvent, CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

var cardTypeId = domainEvent.CardTypeId != 0 ? domainEvent.CardTypeId : 1;

var buyer = await _buyerRepository.FindAsync(domainEvent.UserId);

var buyerExisted = buyer is not null;

if (!buyerExisted)

{

buyer = new Buyer(domainEvent.UserId, domainEvent.UserName);

}

buyer.VerifyOrAddPaymentMethod(

cardTypeId,

$"Payment Method on {DateTime.UtcNow}",

domainEvent.CardNumber,

domainEvent.CardSecurityNumber,

domainEvent.CardHolderName,

domainEvent.CardExpiration,

domainEvent.Order.Id);

var buyerUpdated = buyerExisted ?

_buyerRepository.Update(buyer) :

_buyerRepository.Add(buyer);

await _buyerRepository.UnitOfWork

.SaveEntitiesAsync(cancellationToken);

var integrationEvent = new OrderStatusChangedToSubmittedIntegrationEvent(

domainEvent.Order.Id, domainEvent.Order.OrderStatus.Name, buyer.Name);

await _orderingIntegrationEventService.AddAndSaveEventAsync(integrationEvent);

OrderingApiTrace.LogOrderBuyerAndPaymentValidatedOrUpdated(

_logger, buyerUpdated.Id, domainEvent.Order.Id);

}

}

The previous domain event handler code is considered application layer code because it uses infrastructure repositories, as explained in the next section on the infrastructure-persistence layer. Event handlers could also use other infrastructure components.

Domain events can generate integration events to be published outside of the microservice boundaries

Finally, it's important to mention that you might sometimes want to propagate events across multiple microservices. That propagation is an integration event, and it could be published through an event bus from any specific domain event handler.

Conclusions on domain events

As stated, use domain events to explicitly implement side effects of changes within your domain. To use DDD terminology, use domain events to explicitly implement side effects across one or multiple aggregates. Additionally, and for better scalability and less impact on database locks, use eventual consistency between aggregates within the same domain.

The reference app uses MediatR to propagate domain events synchronously across aggregates, within a single transaction. However, you could also use some AMQP implementation like RabbitMQ or Azure Service Bus to propagate domain events asynchronously, using eventual consistency but, as mentioned above, you have to consider the need for compensatory actions in case of failures.

Additional resources

Greg Young. What is a Domain Event?

https://cqrs.files.wordpress.com/2010/11/cqrs_documents.pdf#page=25Jan Stenberg. Domain Events and Eventual Consistency

https://www.infoq.com/news/2015/09/domain-events-consistencyJimmy Bogard. A better domain events pattern

https://lostechies.com/jimmybogard/2014/05/13/a-better-domain-events-pattern/Vaughn Vernon. Effective Aggregate Design Part II: Making Aggregates Work Together

https://dddcommunity.org/wp-content/uploads/files/pdf_articles/Vernon_2011_2.pdfJimmy Bogard. Strengthening your domain: Domain Events

https://lostechies.com/jimmybogard/2010/04/08/strengthening-your-domain-domain-events/Udi Dahan. How to create fully encapsulated Domain Models

https://udidahan.com/2008/02/29/how-to-create-fully-encapsulated-domain-models/Udi Dahan. Domain Events – Take 2

https://udidahan.com/2008/08/25/domain-events-take-2/Udi Dahan. Domain Events – Salvation

https://udidahan.com/2009/06/14/domain-events-salvation/Cesar de la Torre. Domain Events vs. Integration Events in DDD and microservices architectures

https://devblogs.microsoft.com/cesardelatorre/domain-events-vs-integration-events-in-domain-driven-design-and-microservices-architectures/