Test ASP.NET Core MVC apps

Tip

This content is an excerpt from the eBook, Architect Modern Web Applications with ASP.NET Core and Azure, available on .NET Docs or as a free downloadable PDF that can be read offline.

"If you don't like unit testing your product, most likely your customers won't like to test it, either." _- Anonymous-

Software of any complexity can fail in unexpected ways in response to changes. Thus, testing after making changes is required for all but the most trivial (or least critical) applications. Manual testing is the slowest, least reliable, most expensive way to test software. Unfortunately, if applications aren't designed to be testable, it can be the only means of testing available. Applications written to follow the architectural principles laid out in chapter 4 should be largely unit testable. ASP.NET Core applications support automated integration and functional testing.

Kinds of automated tests

There are many kinds of automated tests for software applications. The simplest, lowest level test is the unit test. At a slightly higher level, there are integration tests and functional tests. Other kinds of tests, such as UI tests, load tests, stress tests, and smoke tests, are beyond the scope of this document.

Unit tests

A unit test tests a single part of your application's logic. One can further describe it by listing some of the things that it isn't. A unit test doesn't test how your code works with dependencies or infrastructure – that's what integration tests are for. A unit test doesn't test the framework your code is written on – you should assume it works or, if you find it doesn't, file a bug and code a workaround. A unit test runs completely in memory and in process. It doesn't communicate with the file system, the network, or a database. Unit tests should only test your code.

Unit tests, by virtue of the fact that they test only a single unit of your code, with no external dependencies, should execute extremely fast. Thus, you should be able to run test suites of hundreds of unit tests in a few seconds. Run them frequently, ideally before every push to a shared source control repository, and certainly with every automated build on your build server.

Integration tests

Although it's a good idea to encapsulate your code that interacts with infrastructure like databases and file systems, you will still have some of that code, and you will probably want to test it. Additionally, you should verify that your code's layers interact as you expect when your application's dependencies are fully resolved. This functionality is the responsibility of integration tests. Integration tests tend to be slower and more difficult to set up than unit tests, because they often depend on external dependencies and infrastructure. Thus, you should avoid testing things that could be tested with unit tests in integration tests. If you can test a given scenario with a unit test, you should test it with a unit test. If you can't, then consider using an integration test.

Integration tests will often have more complex setup and teardown procedures than unit tests. For example, an integration test that goes against an actual database will need a way to return the database to a known state before each test run. As new tests are added and the production database schema evolves, these test scripts will tend to grow in size and complexity. In many large systems, it is impractical to run full suites of integration tests on developer workstations before checking in changes to shared source control. In these cases, integration tests may be run on a build server.

Functional tests

Integration tests are written from the perspective of the developer, to verify that some components of the system work correctly together. Functional tests are written from the perspective of the user, and verify the correctness of the system based on its requirements. The following excerpt offers a useful analogy for how to think about functional tests, compared to unit tests:

"Many times the development of a system is likened to the building of a house. While this analogy isn't quite correct, we can extend it for the purposes of understanding the difference between unit and functional tests. Unit testing is analogous to a building inspector visiting a house's construction site. He is focused on the various internal systems of the house, the foundation, framing, electrical, plumbing, and so on. He ensures (tests) that the parts of the house will work correctly and safely, that is, meet the building code. Functional tests in this scenario are analogous to the homeowner visiting this same construction site. He assumes that the internal systems will behave appropriately, that the building inspector is performing his task. The homeowner is focused on what it will be like to live in this house. He is concerned with how the house looks, are the various rooms a comfortable size, does the house fit the family's needs, are the windows in a good spot to catch the morning sun. The homeowner is performing functional tests on the house. He has the user's perspective. The building inspector is performing unit tests on the house. He has the builder's perspective."

Source: Unit Testing versus Functional Tests

I'm fond of saying "As developers, we fail in two ways: we build the thing wrong, or we build the wrong thing." Unit tests ensure you are building the thing right; functional tests ensure you are building the right thing.

Since functional tests operate at the system level, they may require some degree of UI automation. Like integration tests, they usually work with some kind of test infrastructure as well. This activity makes them slower and more brittle than unit and integration tests. You should have only as many functional tests as you need to be confident the system is behaving as users expect.

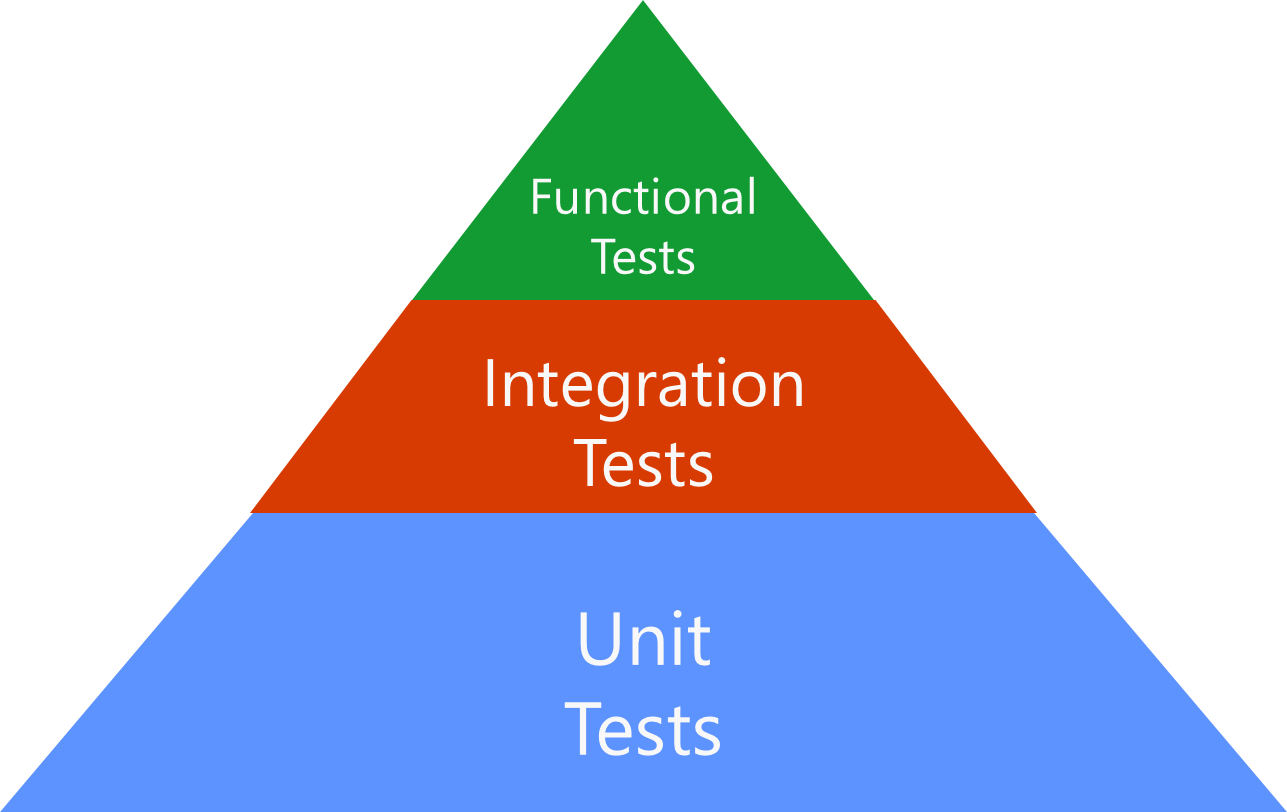

Testing Pyramid

Martin Fowler wrote about the testing pyramid, an example of which is shown in Figure 9-1.

Figure 9-1. Testing Pyramid

The different layers of the pyramid, and their relative sizes, represent different kinds of tests and how many you should write for your application. As you can see, the recommendation is to have a large base of unit tests, supported by a smaller layer of integration tests, with an even smaller layer of functional tests. Each layer should ideally only have tests in it that cannot be performed adequately at a lower layer. Keep the testing pyramid in mind when you are trying to decide which kind of test you need for a particular scenario.

What to test

A common problem for developers who are inexperienced with writing automated tests is coming up with what to test. A good starting point is to test conditional logic. Anywhere you have a method with behavior that changes based on a conditional statement (if-else, switch, and so on), you should be able to come up with at least a couple of tests that confirm the correct behavior for certain conditions. If your code has error conditions, it's good to write at least one test for the "happy path" through the code (with no errors), and at least one test for the "sad path" (with errors or atypical results) to confirm your application behaves as expected in the face of errors. Finally, try to focus on testing things that can fail, rather than focusing on metrics like code coverage. More code coverage is better than less, generally. However, writing a few more tests of a complex and business-critical method is usually a better use of time than writing tests for auto-properties just to improve test code coverage metrics.

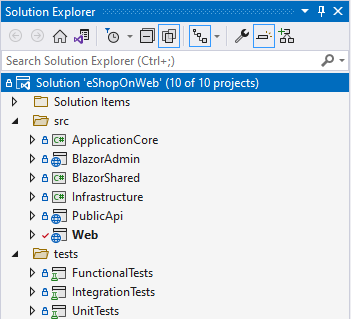

Organizing test projects

Test projects can be organized however works best for you. It's a good idea to separate tests by type (unit test, integration test) and by what they are testing (by project, by namespace). Whether this separation consists of folders within a single test project, or multiple test projects, is a design decision. One project is simplest, but for large projects with many tests, or in order to more easily run different sets of tests, you might want to have several different test projects. Many teams organize test projects based on the project they are testing, which for applications with more than a few projects can result in a large number of test projects, especially if you still break these down according to what kind of tests are in each project. A compromise approach is to have one project per kind of test, per application, with folders inside the test projects to indicate the project (and class) being tested.

A common approach is to organize the application projects under a 'src' folder, and the application's test projects under a parallel 'tests' folder. You can create matching solution folders in Visual Studio, if you find this organization useful.

Figure 9-2. Test organization in your solution

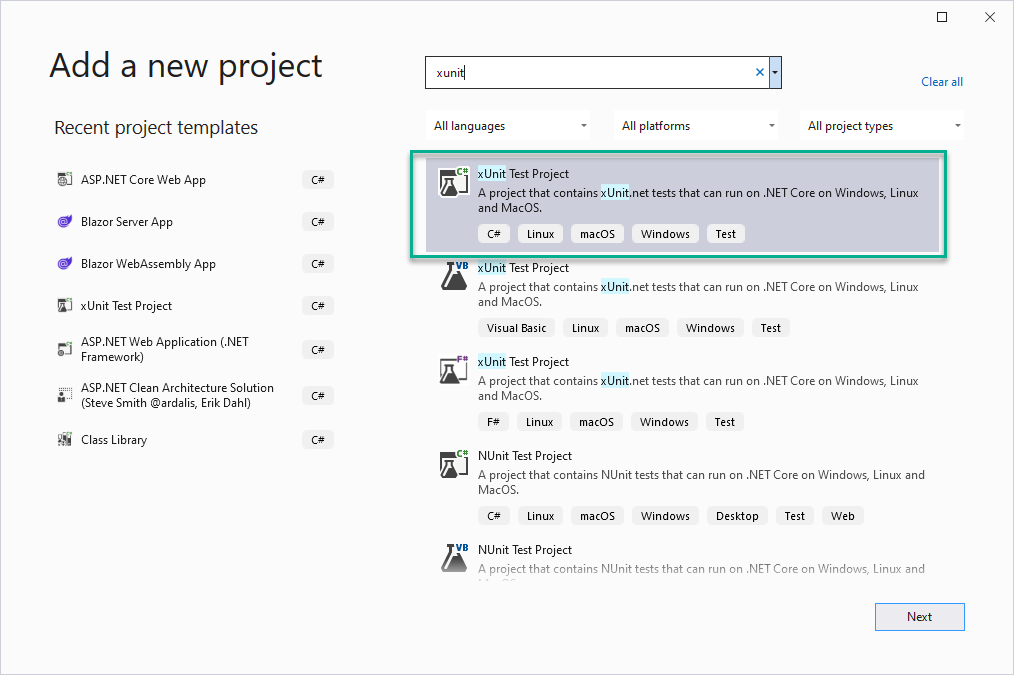

You can use whichever test framework you prefer. The xUnit framework works well and is what all of the ASP.NET Core and EF Core tests are written in. You can add an xUnit test project in Visual Studio using the template shown in Figure 9-3, or from the CLI using dotnet new xunit.

Figure 9-3. Add an xUnit Test Project in Visual Studio

Test naming

Name your tests in a consistent fashion, with names that indicate what each test does. One approach I've had great success with is to name test classes according to the class and method they are testing. This approach results in many small test classes, but it makes it extremely clear what each test is responsible for. With the test class name set up, to identify the class and method to be tested, the test method name can be used to specify the behavior being tested. This name should include the expected behavior and any inputs or assumptions that should yield this behavior. Some example test names:

CatalogControllerGetImage.CallsImageServiceWithIdCatalogControllerGetImage.LogsWarningGivenImageMissingExceptionCatalogControllerGetImage.ReturnsFileResultWithBytesGivenSuccessCatalogControllerGetImage.ReturnsNotFoundResultGivenImageMissingException

A variation of this approach ends each test class name with "Should" and modifies the tense slightly:

CatalogControllerGetImageShould.CallImageServiceWithIdCatalogControllerGetImageShould.LogWarningGivenImageMissingException

Some teams find the second naming approach clearer, though slightly more verbose. In any case, try to use a naming convention that provides insight into test behavior, so that when one or more tests fail, it's obvious from their names what cases have failed. Avoid naming your tests vaguely, such as ControllerTests.Test1, as these names offer no value when you see them in test results.

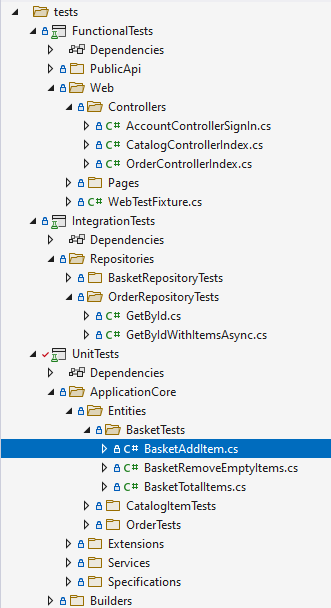

If you follow a naming convention like the one above that produces many small test classes, it's a good idea to further organize your tests using folders and namespaces. Figure 9-4 shows one approach to organizing tests by folder within several test projects.

Figure 9-4. Organizing test classes by folder based on class being tested.

If a particular application class has many methods being tested (and thus many test classes), it may make sense to place these classes in a folder corresponding to the application class. This organization is no different than how you might organize files into folders elsewhere. If you have more than three or four related files in a folder containing many other files, it's often helpful to move them into their own subfolder.

Unit testing ASP.NET Core apps

In a well-designed ASP.NET Core application, most of the complexity and business logic will be encapsulated in business entities and a variety of services. The ASP.NET Core MVC app itself, with its controllers, filters, viewmodels, and views, should require few unit tests. Much of the functionality of a given action lies outside the action method itself. Testing whether routing or global error handling work correctly cannot be done effectively with a unit test. Likewise, any filters, including model validation and authentication and authorization filters, cannot be unit tested with a test targeting a controller's action method. Without these sources of behavior, most action methods should be trivially small, delegating the bulk of their work to services that can be tested independent of the controller that uses them.

Sometimes you'll need to refactor your code in order to unit test it. Frequently this activity involves identifying abstractions and using dependency injection to access the abstraction in the code you'd like to test, rather than coding directly against infrastructure. For example, consider this easy action method for displaying images:

[HttpGet("[controller]/pic/{id}")]

public IActionResult GetImage(int id)

{

var contentRoot = _env.ContentRootPath + "//Pics";

var path = Path.Combine(contentRoot, id + ".png");

Byte[] b = System.IO.File.ReadAllBytes(path);

return File(b, "image/png");

}

Unit testing this method is made difficult by its direct dependency on System.IO.File, which it uses to read from the file system. You can test this behavior to ensure it works as expected, but doing so with real files is an integration test. It's worth noting you can't unit test this method's route—you'll see how to do this testing with a functional test shortly.

If you can't unit test the file system behavior directly, and you can't test the route, what is there to test? Well, after refactoring to make unit testing possible, you may discover some test cases and missing behavior, such as error handling. What does the method do when a file isn't found? What should it do? In this example, the refactored method looks like this:

[HttpGet("[controller]/pic/{id}")]

public IActionResult GetImage(int id)

{

byte[] imageBytes;

try

{

imageBytes = _imageService.GetImageBytesById(id);

}

catch (CatalogImageMissingException ex)

{

_logger.LogWarning($"No image found for id: {id}");

return NotFound();

}

return File(imageBytes, "image/png");

}

_logger and _imageService are both injected as dependencies. Now you can test that the same ID that is passed to the action method is passed to _imageService, and that the resulting bytes are returned as part of the FileResult. You can also test that error logging is happening as expected, and that a NotFound result is returned if the image is missing, assuming this behavior is important application behavior (that is, not just temporary code the developer added to diagnose an issue). The actual file logic has moved into a separate implementation service, and has been augmented to return an application-specific exception for the case of a missing file. You can test this implementation independently, using an integration test.

In most cases, you'll want to use global exception handlers in your controllers, so the amount of logic in them should be minimal and probably not worth unit testing. Do most of your testing of controller actions using functional tests and the TestServer class described below.

Integration testing ASP.NET Core apps

Most of the integration tests in your ASP.NET Core apps should be testing services and other implementation types defined in your Infrastructure project. For example, you could test that EF Core was successfully updating and retrieving the data that you expect from your data access classes residing in the Infrastructure project. The best way to test that your ASP.NET Core MVC project is behaving correctly is with functional tests that run against your app running in a test host.

Functional testing ASP.NET Core apps

For ASP.NET Core applications, the TestServer class makes functional tests fairly easy to write. You configure a TestServer using a WebHostBuilder (or HostBuilder) directly (as you normally do for your application), or with the WebApplicationFactory type (available since version 2.1). Try to match your test host to your production host as closely as possible, so your tests exercise behavior similar to what the app will do in production. The WebApplicationFactory class is helpful for configuring the TestServer's ContentRoot, which is used by ASP.NET Core to locate static resource like Views.

You can create simple functional tests by creating a test class that implements IClassFixture<WebApplicationFactory<TEntryPoint>>, where TEntryPoint is your web application's Startup class. With this interface in place, your test fixture can create a client using the factory's CreateClient method:

public class BasicWebTests : IClassFixture<WebApplicationFactory<Program>>

{

protected readonly HttpClient _client;

public BasicWebTests(WebApplicationFactory<Program> factory)

{

_client = factory.CreateClient();

}

// write tests that use _client

}

Tip

If you're using minimal API configuration in your Program.cs file, by default the class will be declared internal and won't be accessible from the test project. You can choose any other instance class in your web project instead, or add this to your Program.cs file:

// Make the implicit Program class public so test projects can access it

public partial class Program { }

Frequently, you'll want to perform some additional configuration of your site before each test runs, such as configuring the application to use an in-memory data store and then seeding the application with test data. To achieve this functionality, create your own subclass of WebApplicationFactory<TEntryPoint> and override its ConfigureWebHost method. The example below is from the eShopOnWeb FunctionalTests project and is used as part of the tests on the main web application.

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Hosting;

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Identity;

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Mvc.Testing;

using Microsoft.EntityFrameworkCore;

using Microsoft.eShopWeb.Infrastructure.Data;

using Microsoft.eShopWeb.Infrastructure.Identity;

using Microsoft.eShopWeb.Web;

using Microsoft.Extensions.DependencyInjection;

using Microsoft.Extensions.Logging;

using System;

namespace Microsoft.eShopWeb.FunctionalTests.Web;

public class WebTestFixture : WebApplicationFactory<Startup>

{

protected override void ConfigureWebHost(IWebHostBuilder builder)

{

builder.UseEnvironment("Testing");

builder.ConfigureServices(services =>

{

services.AddEntityFrameworkInMemoryDatabase();

// Create a new service provider.

var provider = services

.AddEntityFrameworkInMemoryDatabase()

.BuildServiceProvider();

// Add a database context (ApplicationDbContext) using an in-memory

// database for testing.

services.AddDbContext<CatalogContext>(options =>

{

options.UseInMemoryDatabase("InMemoryDbForTesting");

options.UseInternalServiceProvider(provider);

});

services.AddDbContext<AppIdentityDbContext>(options =>

{

options.UseInMemoryDatabase("Identity");

options.UseInternalServiceProvider(provider);

});

// Build the service provider.

var sp = services.BuildServiceProvider();

// Create a scope to obtain a reference to the database

// context (ApplicationDbContext).

using (var scope = sp.CreateScope())

{

var scopedServices = scope.ServiceProvider;

var db = scopedServices.GetRequiredService<CatalogContext>();

var loggerFactory = scopedServices.GetRequiredService<ILoggerFactory>();

var logger = scopedServices

.GetRequiredService<ILogger<WebTestFixture>>();

// Ensure the database is created.

db.Database.EnsureCreated();

try

{

// Seed the database with test data.

CatalogContextSeed.SeedAsync(db, loggerFactory).Wait();

// seed sample user data

var userManager = scopedServices.GetRequiredService<UserManager<ApplicationUser>>();

var roleManager = scopedServices.GetRequiredService<RoleManager<IdentityRole>>();

AppIdentityDbContextSeed.SeedAsync(userManager, roleManager).Wait();

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

logger.LogError(ex, $"An error occurred seeding the " +

"database with test messages. Error: {ex.Message}");

}

}

});

}

}

Tests can make use of this custom WebApplicationFactory by using it to create a client and then making requests to the application using this client instance. The application will have data seeded that can be used as part of the test's assertions. The following test verifies that the home page of the eShopOnWeb application loads correctly and includes a product listing that was added to the application as part of the seed data.

using Microsoft.eShopWeb.FunctionalTests.Web;

using System.Net.Http;

using System.Threading.Tasks;

using Xunit;

namespace Microsoft.eShopWeb.FunctionalTests.WebRazorPages;

[Collection("Sequential")]

public class HomePageOnGet : IClassFixture<WebTestFixture>

{

public HomePageOnGet(WebTestFixture factory)

{

Client = factory.CreateClient();

}

public HttpClient Client { get; }

[Fact]

public async Task ReturnsHomePageWithProductListing()

{

// Arrange & Act

var response = await Client.GetAsync("/");

response.EnsureSuccessStatusCode();

var stringResponse = await response.Content.ReadAsStringAsync();

// Assert

Assert.Contains(".NET Bot Black Sweatshirt", stringResponse);

}

}

This functional test exercises the full ASP.NET Core MVC / Razor Pages application stack, including all middleware, filters, and binders that may be in place. It verifies that a given route ("/") returns the expected success status code and HTML output. It does so without setting up a real web server, and avoids much of the brittleness that using a real web server for testing can experience (for example, problems with firewall settings). Functional tests that run against TestServer are usually slower than integration and unit tests, but are much faster than tests that would run over the network to a test web server. Use functional tests to ensure your application's front-end stack is working as expected. These tests are especially useful when you find duplication in your controllers or pages and you address the duplication by adding filters. Ideally, this refactoring won't change the behavior of the application, and a suite of functional tests will verify this is the case.

References – Test ASP.NET Core MVC apps

- Testing in ASP.NET Core

https://zcusa.951200.xyz/aspnet/core/testing/- Unit Test Naming Convention

https://ardalis.com/unit-test-naming-convention- Testing EF Core

https://zcusa.951200.xyz/ef/core/miscellaneous/testing/- Integration tests in ASP.NET Core

https://zcusa.951200.xyz/aspnet/core/test/integration-tests