Evaluate financial considerations

Measuring objectives and identifying the return expected from a specific objective can help you to define a financial consideration. Cost is another key financial consideration. In this unit, we explore various outcome-driven considerations, a few formulas to calculate costs, and how organizations can reduce capital expenditures.

Understand your financial stories

A fundamental shift in the IT operating model drives The core financial benefits of Azure. This shift benefits your organization's core financial statements and frees up cash flow for reinvestment:

Balance sheet: When you operate on-premises in datacenters, you might have invested up front in long-term assets that limit the cash and capital required to grow your business. While in the cloud, you can shift datacenter operations costs into modernization, developing cloud applications, and other projects that drive business growth. This shift can make your balance sheet more agile.

Cash flow statement: The pay-for-what-you-consume model and the ability to apply policies and tags to your Azure resources can help you improve the predictability of your cash flow statement. This model improves the timing of your cash flow by delaying spend.

Income statement (profit and loss): You can improve profitability over time by taking advantage of Azure's flexibility, low management costs, services, and pricing models.

Common finance vocabulary terms

Use these common finance terms when your team is creating a cloud migration business case. These terms can help when you share your business case with a finance team.

Terms

Amortization: An expense tied to a typically intangible asset that reflects the economic usage of that asset in a particular time period. For example, if you purchase a license worth USD100, you'd capitalize that on your balance sheet. If you amortized it over five years, you'd annually recognize an expense of USD20 per year that impacts your income statement.

Balance sheet: A balance sheet is a financial statement that reports a company's assets, liabilities, and shareholders' equity as of a specific date.

Capital Expense (CAPEX): The upfront investment in equipment. This equipment is capitalized as an asset and put on your balance sheet.

Cash flow statement: A cash flow statement is a financial statement that summarizes the amount of cash and cash equivalents entering and leaving a company during a given period.

Cloud economics: An understanding of the benefits and costs of the cloud, and the financial impact when you start a migration from on-premises to cloud computing.

Depreciation: An expense tied to a capitalized asset that reflects the economic usage of that asset in a particular time period. For example, if you purchase a server worth USD100, you'd capitalize that on your balance sheet. If you depreciated it over five years, you'd annually recognize an expense of USD20 per year that impacts your income statement.

Double-mortgage period: A period when you have two sets of costs at the same time. For example, when you have both on-premises and cloud costs.

Earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA): A performance indicator of the profitability of a business. This metric starts from operating income, which is the income from your ongoing business operations (ignoring things like taxes or interest expense) and adds back depreciation and amortization. While a useful performance metric that's used for comparability, it's often viewed along with metrics like Capital Expenditure to have a better all-up understanding of a company's ability to generate free cash flow.

Net Present Value (NPV): An assessment of the financial value of a business investment. This metric looks at cash flows, timing, and the required interest rate.

Operating Expense (OPEX): The ongoing expenses for a business. For example, a maintenance payment or periodic bill for Azure services.

Profit and Loss (P&L): A financial statement that summarizes the revenues, costs, and expenses incurred over a specified period, usually a fiscal quarter or year. It's also referred to as the income statement.

Return on Investment (ROI): Return on investment (ROI) is a metric used to understand the profitability of an investment. ROI compares how much you paid for an investment to how much you earned to evaluate its efficiency.

Sample outcomes by category

Speaking in terms of business outcomes can feel like a foreign language to many technical-minded individuals. To help ease translation, we have curated a set of business outcome examples. You can use the following examples to inspire and demonstrate business outcomes that are based on actual transformation journeys.

To help you find specific types of examples of business outcomes, we've separated our list of examples into categories. This approach tends to drive consensus-building conversations across business units.

Fiscal outcomes: Financial or fiscal performance is the cleanest business outcome for many business leaders, but it's not the only one.

View samples of fiscal outcomes.

Agility outcomes: Today's fast-changing business environment places a premium on time. The ability to respond to and drive market change quickly is the fundamental measure of business agility.

View samples of agility outcomes.

Reach outcomes: In a constantly shrinking market, you can measure global reach (the ability to support global customers and users) by compliance in geographies that are relevant to the business.

View outcomes related to global reach.

Customer engagement outcomes: Social marketplaces are redefining winners and losers at an unheard-of pace. Responding to user needs is a key measure of customer engagement.

Learn more about customer engagement outcomes.

Performance outcomes: Performance and reliability are assumed. When either falters, reputation damage can be painful and long-lasting.

Learn more about performance outcomes.

Sustainability goals: Organizations are increasingly discussing environmental goals and sustainability targets.

Learn more about sustainability goals.

Create a financial model for cloud transformation

Creating a financial model that accurately represents the full business value of any cloud transformation can be complicated. Financial models and business justifications tend to vary for different organizations. This unit establishes some formulas and points out a few things that often are missed when strategists create financial models.

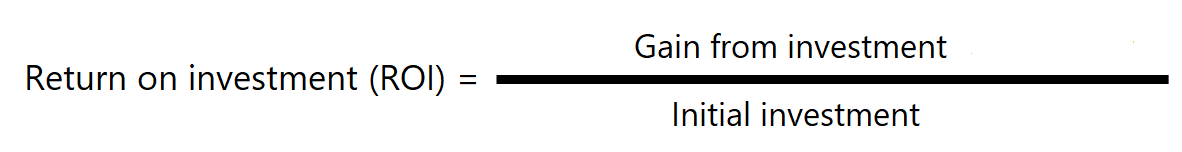

Return on investment

Return on investment (ROI) often is an important criteria for the C-suite or the board of directors. ROI is used to compare different ways to invest limited capital resources. The formula for ROI is fairly simple. The details you need to create each input to the formula might not be as simple, though. Essentially, ROI is the amount of return produced from an initial investment. ROI usually is represented as a percentage:

In the next sections, we'll walk through the data you'll need to calculate the initial investment and the gain from investment (earnings).

Calculate initial investment

Initial investment is the capital expense and the operating expense that's required to complete a transformation. Even though the classification of costs can vary depending on accounting models and CFO preference, this category includes items like professional services that are required to complete the transformation, software licenses used only during the transformation, and the cost of cloud services during the transformation. It can also potentially include the cost of salaried employees during the transformation.

Add these costs to create an estimate of the initial investment.

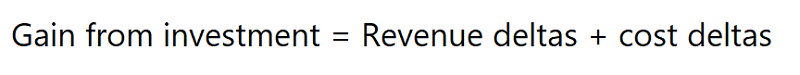

Calculate the gain from investment

Calculating the gain from investment often requires a second formula that's specific to the business outcomes and associated technical changes. Calculating earnings is harder than calculating cost reductions.

To calculate earnings, you need two variables:

- Changes (deltas) in revenue

- Changes in costs

These variables are described in the following sections:

Revenue deltas

Revenue deltas should be forecast in partnership with business stakeholders. After the business stakeholders agree on a revenue impact, the agreement can be used to improve the earnings position.

Cost deltas

Cost deltas are the increase or decrease in costs caused by the transformation. Independent variables can affect cost deltas. Earnings largely are based on hard costs like capital expense reductions, cost avoidance, operational cost reductions, and depreciation reductions. The following sections describe some cost deltas to consider.

Depreciation reduction or acceleration

For guidance on depreciation, speak with the CFO or finance team. The following information is meant to serve as a general reference on the article of depreciation.

When capital is invested in the acquisition of an asset, that investment might be used for financial or tax purposes to produce ongoing benefits over the expected lifespan of the asset. Some companies see depreciation as a positive tax advantage. Others see it as a committed, ongoing expense that's similar to other recurring expenses attributed to the annual IT budget.

Speak with the finance office to find out whether eliminating depreciation is possible and whether the depreciation elimination would make a positive contribution to cost deltas.

Physical asset recovery

In some cases, retired assets can be sold as a source of revenue. This revenue often is lumped into cost reduction for simplicity. But selling retired assets truly can be an increase in revenue, and the revenue can be taxed. Speak with the finance office to understand the viability of this option and how to account for the resulting revenue.

Operational cost reductions

Recurring expenses that are required to operate a business often are called operating expenses. This category is broad. In most accounting models, this expense category includes:

- Software licensing

- Internet hosting expenses

- Electric bills

- Real estate rentals

- Cooling expenses

- Temporary staff required for operations

- Equipment rentals

- Replacement parts

- Maintenance contracts

- Repair services

- Business continuity and disaster recovery services

- Other expenses that don't require capital expense approvals

This category provides one of the highest earning deltas. When you're considering a cloud migration, time invested in making this list exhaustive rarely is wasted. Ask the CIO and finance team questions to ensure that all operational costs are accounted for.

Cost avoidance

When an operating expenditure is expected but not yet in an approved budget, the expenditure might not fit into a cost reduction category. For example, if VMware and Microsoft licenses need to be renegotiated and paid next year, they aren't fully qualified costs yet. Reductions in those expected costs are treated like operational costs for the sake of cost delta calculations. Informally, however, they should be referred to as cost avoidance until negotiation and budget approval is complete.

Soft-cost reductions

At some companies, soft costs like reductions in operational complexity or reductions in full-time staff for operating a datacenter might also be included in cost deltas. But including soft costs might not be a good idea. When you include soft-cost reductions, you insert an undocumented assumption that the reduction creates tangible cost savings. Technology projects rarely result in actual soft-cost recovery.

Headcount reductions

Time savings for staff often are included in soft-cost reductions. When those time savings map to actual reductions in IT salary or staffing, they might be calculated separately as headcount reductions.

That said, skills that are needed to work on-premises generally map to a similar (or higher-level) skill set that's needed to work in the cloud. So, people generally aren't laid off after a cloud migration.

An exception occurs when operational capacity is provided by a third party or an Azure Expert Managed Services Provider (MSP). If a third party manages IT systems, a cloud-native solution or cloud-native MSP could replace the operating costs. A cloud-native MSP can operate more efficiently and potentially at a lower cost. If that's the case, operational cost reductions belong in hard-cost calculations.

Capital expense reductions or avoidance

Capital expenses are slightly different from operating expenses. Generally, datacenter expansion or refresh cycles drive this category. A datacenter expansion example is the cost of a new high-performance cluster to host a big data solution or data warehouse. This expense generally would fit into a capital expense category.

More common are basic equipment refresh cycles. Some companies have rigid hardware refresh cycles, which means that assets are retired and replaced on a regular cycle (usually every three, five, or eight years). These cycles often coincide with asset lease cycles or with the forecasted life span of equipment. In a new refresh cycle, IT draws on capital expense to acquire new equipment.

If a refresh cycle is approved and budgeted, a cloud transformation might help eliminate that cost. If a refresh cycle is planned but not yet approved, the cloud transformation might avoid a capital expenditure. Both reductions would be added to the cost delta.

What is cloud accounting?

The cloud changes how IT accounts for costs. Various IT accounting models are easier to support because of how the cloud allocates costs, so it's important to understand how to account for cloud costs before you begin a cloud-transformation journey. This article outlines the most common cloud accounting models for IT.

Traditional IT accounting (cost-center model)

It's often accurate to consider IT a cost center. In the traditional IT accounting model, IT consolidates purchasing power for all IT assets. As we pointed out in the financial models article, that purchasing power consolidation can include software licenses, recurring charges for CRM licensing, purchase of employee desktops, and other large costs.

When IT serves as a cost center, the perceived value of IT is largely viewed through a procurement-management lens. This perception makes it difficult for the board or other executives to understand the true value that IT provides. Procurement costs tend to skew the view of IT by outweighing any other value added by the organization. This view explains why IT is often lumped into the responsibilities of either the chief financial officer or the chief operating officer. This perception of IT is limited and might be shortsighted.

Central IT accounting (profit-center model)

To overcome the cost-center view of IT, some CIOs opted for a centralized IT model of accounting. In this type of model, IT is treated like a competing business unit and a peer to revenue-producing business units. In some cases, this model can be entirely logical. For example, some organizations have a professional IT services division that generates a revenue stream. Frequently, centralized IT models don't generate significant revenue, making it difficult to justify the model.

Regardless of the revenue model, centralized IT accounting models are unique because of how the IT unit accounts for costs. In a traditional IT model, the IT team records costs and pays those costs from shared funds like operations and maintenance (O&M) or a dedicated profit and loss (P&L) account.

In a central IT accounting model, the IT team marks up the services provided to account for overhead, management, and other estimated expenses. It then bills the competing business units for the marked-up services. In this model, the CIO is expected to manage the P&L associated with the sale of those services. This model can create inflated IT costs and contention between central IT and business units. Especially, when IT needs to cut costs or isn't meeting agreed-upon SLAs. During times of technology or market change, any new technology would cause a disruption to central IT's P&L, making transformation difficult.

Chargeback

One of the common first steps in changing IT's reputation as a cost center is implementing a chargeback model of accounting. This model is especially common in smaller enterprises or highly efficient IT organizations. In the chargeback model, any IT costs that are associated with a specific business unit are treated like an operating expense in that business unit's budget. This practice reduces the cumulative cost effects on IT, allowing business values to show more clearly.

In a legacy on-premises model, chargeback is difficult to realize because someone still has to carry the large capital expenses and depreciation. The ongoing conversion from capital expenditures to operating expenses associated with usage is a difficult accounting exercise. This difficulty is a major reason for the creation of the traditional IT accounting model and the central IT accounting model. The operating-expenses model of cloud cost accounting is almost required if you want to efficiently deliver a chargeback model.

However, you shouldn't implement this model without considering the implications. Here are a few consequences that are unique to a chargeback model:

Chargeback results in a massive reduction of the overall IT budget. For IT organizations that are inefficient or require extensive complex technical skills in operations or maintenance, this model can expose those expenses in an unhealthy way.

Loss of control is a common consequence. In highly political environments, chargeback can result in loss of control and staff being reallocated to the business. This situation could create significant inefficiencies and reduce IT's ability to consistently meet SLAs or project requirements.

Difficulty with accounting for shared services is another common consequence. If the organization is carrying technical debt as a result of growing through acquisition, it's likely that a high percentage of shared services must be maintained to keep all systems working together effectively.

Cloud transformations include solutions to these and other consequences associated with a chargeback model, but each of those solutions includes implementation and operating expenses. The CIO and CFO should carefully weigh the pros and cons of a chargeback model before considering one.

Showback or awareness-back

For larger enterprises, a showback or awareness-back model is a safer first step in the transition from cost center to value center. This model doesn't affect financial accounting. In fact, the P&Ls of each organization don't change. The biggest shift is in mindset and awareness. In a showback or awareness-back model, IT manages the centralized, consolidated buying power as an agent for the business. In reports back to the business, IT attributes any direct costs to the relevant business unit, which reduces the perceived budget directly consumed by IT. IT also plans budgets based on the needs of the associated business units, which allows IT to more accurately account for costs associated with purely IT initiatives.

This model provides a balance between a true chargeback model and more traditional models of IT accounting.

Cloud accounting tools

There are several valuable tools you can use to project the costs involved in migrating to the cloud up front. Predicting and estimating costs provides your organization with KPIs you can later use to compare predicted versus actual costs once you’ve completed your cloud migration.

Azure Pricing Calculator: Use the Azure Pricing Calculator to configure and estimate the costs for Azure products.

Try the Azure Pricing Calculator here.

Azure Virtual Machine (VM) Cost Estimator: The Azure VM Cost Estimator is a Power BI template that allows you to estimate your cost savings against pay-as-you-go pricing. It shows you how to optimize Azure offers and benefits for VMs, like Azure Hybrid Benefit and reserved instances. When you’re evaluating large-scale data centers of more than a hundred compute units, it can be challenging to use the web-based Azure Pricing Calculator because it requires you to input a significant number of technical criteria. The Azure VM Cost Estimator includes an Excel file that feeds data into the Power BI template. This file allows you to input a larger list of criteria, along with more technical specifications. For example, the number of cores assigned to a specific compute unit or the memory footprint and associated utilization. You can even specify the currency value you want the price list generated in, and the different Azure targets you want to place your workloads in. In that way, the Azure VM Cost Estimator helps you automate the cloud cost estimation process.

Download the following files to use the Power BI model:

Impact of cloud accounting models

The choice of accounting models is crucial in system design. The choice of accounting model can affect subscription strategies, naming standards, tagging standards, and policy and blueprint designs.

After you've worked with the business to make decisions about a cloud accounting model and global markets, you can learn more about how to achieve more with your investment in the cloud.

Record your observations

If you haven't already, download the Cloud Adoption Framework Strategy and Plan template. Under Business justification, use the financial considerations that are discussed in this unit to describe your business justification or financial considerations.