What is superposition in quantum computing?

If the cat from the previous unit was a quantum cat, the state of the quantum cat and the box system would be the same: the sum of the six different positions of the quantum cat with respect to the box, weighted by the probability of finding the quantum cat in that position. The only difference is that the classic cat can be in one (and only one) of six possible positions while the quantum cat can be in all six positions at the same time!

In the classical world, objects can only be in one state at a time. However, in the quantum world, quantum particles can be in multiple states at the same time. This phenomenon is called superposition.

In quantum computing nobody uses quantum cats - sadly - but qubits. The word "qubit" means "quantum bit". Just like in classical computing, where the basic unit of information is the bit, in quantum computing the basic unit of information is the qubit. And just like the bit can take two possible values, 0 and 1, a qubit is any quantum particle that can be in two possible states. For example, a qubit could be a photon, which can be polarized in two directions, or an electron, which can be in two energy levels.

How can you represent the superposition in a qubit? What is the probability of finding a qubit in a particular state?

How can you represent the superposition in a qubit?

A qubit is a quantum particle that has two possible positions, or states. As analog to the classical bit, the quantum states of a qubit are also called $0$ and $1$. A qubit can be in the state $0$, in the state $1$, and in any superposition of both states. How can you represent this superposition?

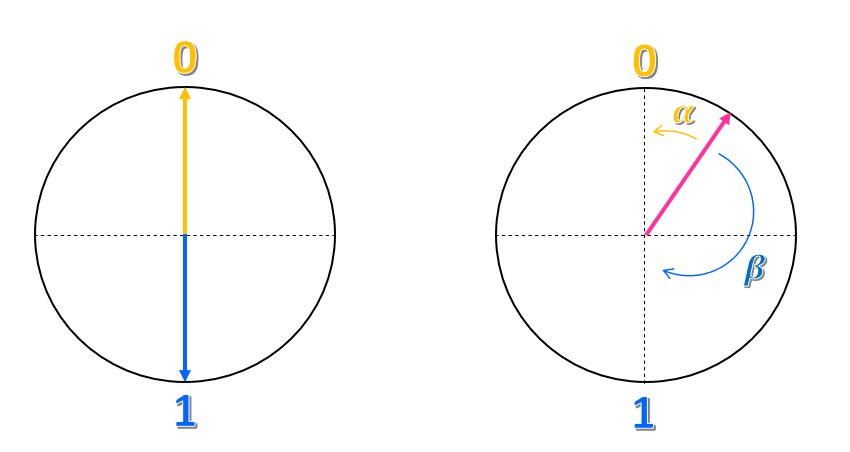

Imagine that you draw a circle and a vertical and horizontal axis such that the middle point is the center of the circle. The state $0$ is placed at the upper point of the vertical axis and the state $1$ is at the lower point.

How could you describe this representation? You could say that the state $0$ is an arrow, or a vector, pointing up and the state $1$ is a vector pointing down. Therefore a classical bit would be a vector pointing either up or down, but never in another direction.

What about any other point of the circle? How can you represent that state? Just as coordinates in a plane, you could try to represent it as a combination of the two states $0$ and $1$. For example, you could take how close the vector is from the state $0$ and call this angle $\alpha$, and how close is from the state $1$ and call this angle $\beta$. We could represent the state as $\alpha 0 + \beta 1 $. Thus, the state is a superposition of the states $0$ and $1$.

Just like the example of the cat and the box, the global state of a qubit is the sum of the individual states, $0$ and $1$, weighted by the probability of finding the qubit in that state, $\alpha$ and $\beta $.

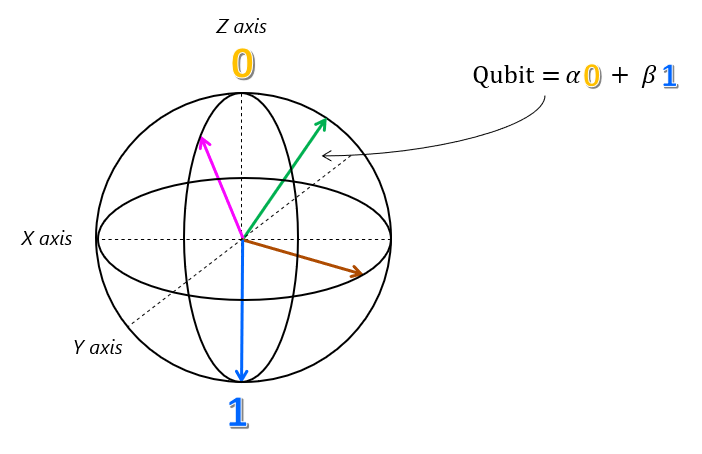

This representation of a qubit is actually accurate, and it's known as the Bloch sphere.

Tip

The Bloch sphere is a powerful tool as the operations that we can perform on a qubit can be represented as rotations about one of the cardinal axes. While thinking about a quantum computation as a sequence of rotations is a powerful intuition, it is challenging to use this intuition to design and describe algorithms. Q# alleviates this issue by providing a language for describing such rotations.

What is the probability of finding a qubit in a state?

Like in the example of the cat and the box of the previous unit, the global state of a qubit is the sum of the individual states, $0$ and $1$, weighted by the probability of finding the qubit in that state, $\alpha$ and $\beta $. The numbers $\alpha$ and $\beta$ represent how "close" the qubit state is to the states $0$ and $1$, respectively. So, are $\alpha$ and $\beta$ the probability of finding the qubit in the state $0$ or $1$? Not exactly.

The numbers $\alpha$ and $\beta$ are probability amplitudes for each state. Their absolute values, for example $|\alpha|^2$ give the corresponding probabilities. For example, the probability for observing state $0$ is $|\alpha|^2$, and the probability of observing state $1$ is $|\beta|^2$.

The numbers $\alpha$ and $\beta$ can be positive, negative, or even complex numbers. However, in a valid quantum superposition, all probabilities must sum to one: $|\alpha|^2+|\beta|^2=1$. This constraint is known as the normalization condition. You can think of the normalization condition as the fact that you always obtain an outcome when you measure, so the probabilities of measuring every possible outcome must sum to one.