Get started with Database Engine permissions

Applies to:

SQL Server

Azure SQL Database

Azure SQL Managed Instance

Azure Synapse Analytics

Analytics Platform System (PDW)

SQL database in Microsoft Fabric

This article reviews some basic security concepts and then describes a typical implementation of the permissions. Permissions in the Database Engine are managed at the server level through logins and server roles, and at the database level through database users and database roles.

The model for SQL Database and SQL database in Microsoft Fabric exposes the same system within each database, but the server level permissions aren't available.

- In SQL Database, see Tutorial: Secure a database in Azure SQL Database. Microsoft Entra ID authentication is recommended. For more information, see Tutorial: Create Microsoft Entra users using Microsoft Entra applications.

- In SQL database in Microsoft Fabric, Microsoft Entra ID for database users is the only supported authentication method. Server-level roles and permissions are not available, only database-level. For more information, see Authorization in SQL database in Microsoft Fabric.

Note

Microsoft Entra ID was previously known as Azure Active Directory (Azure AD).

Security principals

Security principal is the official name of the identities that use SQL Server and that can be assigned permission to take actions. They are usually people or groups of people, but can be other entities that pretend to be people. The security principals can be created and managed using the Transact-SQL listed, or by using SQL Server Management Studio.

Logins

Logins are individual user accounts for logging on to the SQL Server Database Engine. SQL Server and SQL Database support logins based on Windows authentication and logins based on SQL Server authentication. For information about the two types of logins, see Choose an Authentication Mode.

Fixed server roles

In SQL Server, fixed server roles are a set of pre-configured roles that provide convenient group of server-level permissions. Logins can be added to the roles using the ALTER SERVER ROLE ... ADD MEMBER statement. For more information, see ALTER SERVER ROLE (Transact-SQL). SQL Database doesn't support the fixed server roles, but has two roles in the master database (dbmanager and loginmanager) that act like server roles.

User-defined server roles

In SQL Server, you can create your own server roles and assign server-level permissions to them. Logins can be added to the server roles using the ALTER SERVER ROLE ... ADD MEMBER statement. For more information, see ALTER SERVER ROLE (Transact-SQL). SQL Database doesn't support the user-defined server roles.

Database users

Logins are granted access to a database by creating a database user in a database and mapping that database user to sign in. Typically the database user name is the same as the login name, though it doesn't have to be the same. Each database user maps to a single login. A login can be mapped to only one user in a database, but can be mapped as a database user in several different databases.

Database users can also be created that don't have a corresponding login. These users are called contained database users. Microsoft encourages the use of contained database users because it makes it easier to move your database to a different server. Like a login, a contained database user can use either Windows authentication or SQL Server authentication. For more information, see Contained Database Users - Making Your Database Portable.

There are 12 types of users with slight differences in how they authenticate, and who they represent. To see a list of users, see CREATE USER (Transact-SQL).

Fixed database roles

Fixed database roles are a set of pre-configured roles that provide convenient group of database-level permissions. Database users and user-defined database roles can be added to the fixed database roles using the ALTER ROLE ... ADD MEMBER statement. For more information, see ALTER ROLE (Transact-SQL).

User-defined database roles

Users with the CREATE ROLE permission can create new user-defined database roles to represent groups of users with common permissions. Typically permissions are granted or denied to the entire role, simplifying permissions management and monitoring. Database users can be added to the database roles by using the ALTER ROLE ... ADD MEMBER statement. For more information, see ALTER ROLE (Transact-SQL).

Other principals

Additional security principals not discussed here include application roles, and logins and users based on certificates or asymmetric keys.

For a graphic showing the relationships between Windows users, Windows groups, logins, and database users, see Create a Database User.

Typical scenario

The following example represents a common and recommended method of configuring permissions.

In Windows Active Directory or Microsoft Entra ID

Create a user for each person.

Create Windows groups that represent the work units and the work functions.

Add the Windows users to the Windows groups.

If the person connecting will be connecting to many databases

Create a login for the Windows groups. (If using SQL Server authentication, skip the Active Directory steps, and create SQL Server authentication logins here.)

In the user database, create a database user for the login representing the Windows groups.

In the user database, create one or more user-defined database roles, each representing a similar function. For example financial analyst, and sales analyst.

Add the database users to one or more user-defined database roles.

Grant permissions to the user-defined database roles.

If the person connecting will be connecting to only one database

In the user database, create a contained database user for the Windows group. (If using SQL Server authentication, skip the Active Directory steps, and create contained database user SQL Server authentication here.

In the user database, create one or more user-defined database roles, each representing a similar function. For example financial analyst, and sales analyst.

Add the database users to one or more user-defined database roles.

Grant permissions to the user-defined database roles.

The typical result at this point is that a Windows user is a member of a Windows group. The Windows group has a login in SQL Server or SQL Database. The login is mapped to a user identity in the user-database. The user is a member of a database role. Now you need to add permissions to the role.

Assign permissions

Most permission statements have the format:

AUTHORIZATION PERMISSION ON SECURABLE::NAME TO PRINCIPAL;

AUTHORIZATIONmust beGRANT,REVOKEorDENY.The

PERMISSIONestablishes what action is allowed or prohibited. The exact number of permissions differs between SQL Server and SQL Database. The permissions are listed in the article Permissions (Database Engine) and in the chart referenced below.ON SECURABLE::NAMEis the type of securable (server, server object, database, or database object) and its name. Some permissions don't requireON SECURABLE::NAMEbecause it is unambiguous or inappropriate in the context. For example, theCREATE TABLEpermission doesn't require theON SECURABLE::NAMEclause (GRANT CREATE TABLE TO Mary;allows Mary to create tables).PRINCIPALis the security principal (login, user, or role) which receives or loses the permission. Grant permissions to roles whenever possible.

The following example grant statement, grants the UPDATE permission on the Parts table or view that is contained in the Production schema to the role named PartsTeam:

GRANT UPDATE ON OBJECT::Production.Parts TO PartsTeam;

The following example grant statement grants the UPDATE permission on the Production schema, and by extension on any table or view contained within this schema to the role named ProductionTeam, which is a more effective and salable approach to assigning permissions than on individual object-level:

GRANT UPDATE ON SCHEMA::Production TO ProductionTeam;

Permissions are granted to security principals (logins, users, and roles) by using the GRANT statement. Permissions are explicitly denied by using the DENY command. A previously granted or denied permission is removed by using the REVOKE statement. Permissions are cumulative, with the user receiving all the permissions granted to the user, login, and any group memberships; however any permission denial overrides all grants.

Tip

A common mistake is to attempt to remove a GRANT by using DENY instead of REVOKE. This can cause problems when a user receives permissions from multiple sources; which is quite common. The following example demonstrates the principal.

The Sales group receives SELECT permissions on the OrderStatus table through the statement GRANT SELECT ON OBJECT::OrderStatus TO Sales;. User Jae is a member of the Sales role. Jae has also been granted SELECT permission to the OrderStatus table under their own user name through the statement GRANT SELECT ON OBJECT::OrderStatus TO Jae;. Presume the administer wishes to remove the GRANT to the Sales role.

If the administrator correctly executes

REVOKE SELECT ON OBJECT::OrderStatus TO Sales;, then Jae will retainSELECTaccess to the OrderStatus table through their individualGRANTstatement.If the administrator incorrectly executes

DENY SELECT ON OBJECT::OrderStatus TO Sales;then Jae, as a member of the Sales role, will be denied theSELECTpermission because theDENYto Sales overrides their individualGRANT.

Note

Permissions can be configured using Management Studio. Find the securable in Object Explorer, right-click the securable, and then select Properties. Select the Permissions page. For help on using the permission page, see Permissions or Securables Page.

Permission hierarchy

Permissions have a parent/child hierarchy. That is, if you grant SELECT permission on a database, that permission includes SELECT permission on all (child) schemas in the database. If you grant SELECT permission on a schema, it includes SELECT permission on all the (child) tables and views in the schema. The permissions are transitive; that is, if you grant SELECT permission on a database, it includes SELECT permission on all (child) schemas, and all (grandchild) tables and views.

Permissions also have covering permissions. The CONTROL permission on an object, normally gives you all other permissions on the object.

Because both the parent/child hierarchy and the covering hierarchy can act on the same permission, the permission system can get complicated. For example, let's take a table (Region), in a schema (Customers), in a database (SalesDB).

CONTROLpermission on table Region includes all the other permissions on the table Region, includingALTER,SELECT,INSERT,UPDATE,DELETE, and some other permissions.SELECTon the Customers schema that owns the Region table includes theSELECTpermission on the Region table.

So SELECT permission on the Region table can be achieved through any of these six statements:

GRANT SELECT ON OBJECT::Region TO Jae;

GRANT CONTROL ON OBJECT::Region TO Jae;

GRANT SELECT ON SCHEMA::Customers TO Jae;

GRANT CONTROL ON SCHEMA::Customers TO Jae;

GRANT SELECT ON DATABASE::SalesDB TO Jae;

GRANT CONTROL ON DATABASE::SalesDB TO Jae;

Grant the least permission

The first permission listed above (GRANT SELECT ON OBJECT::Region TO Jae;) is the most granular, that is, that statement is the least permission possible that grants the SELECT. No permissions to subordinate objects come with it. It's a good principle to always grant the least permission possible (you can read more about the Principle of Least Privilege), but at the same time (contradicting that) try to grant at higher levels in order to simplify the granting system. So if Jae needs permissions to the entire schema, grant SELECT once at the schema level, instead of granting SELECT at the table or view level many times. The design of the database can dramatically affect how successful this strategy can be. This strategy will work best when your database is designed so that objects needing identical permissions are included in a single schema.

Tip

When designing a database and its objects, from the beginning, plan who or which applications will access which objects and based on that place objects, namely tables but also views, functions and stored procedures in schemas according to buckets of access type as much as possible.

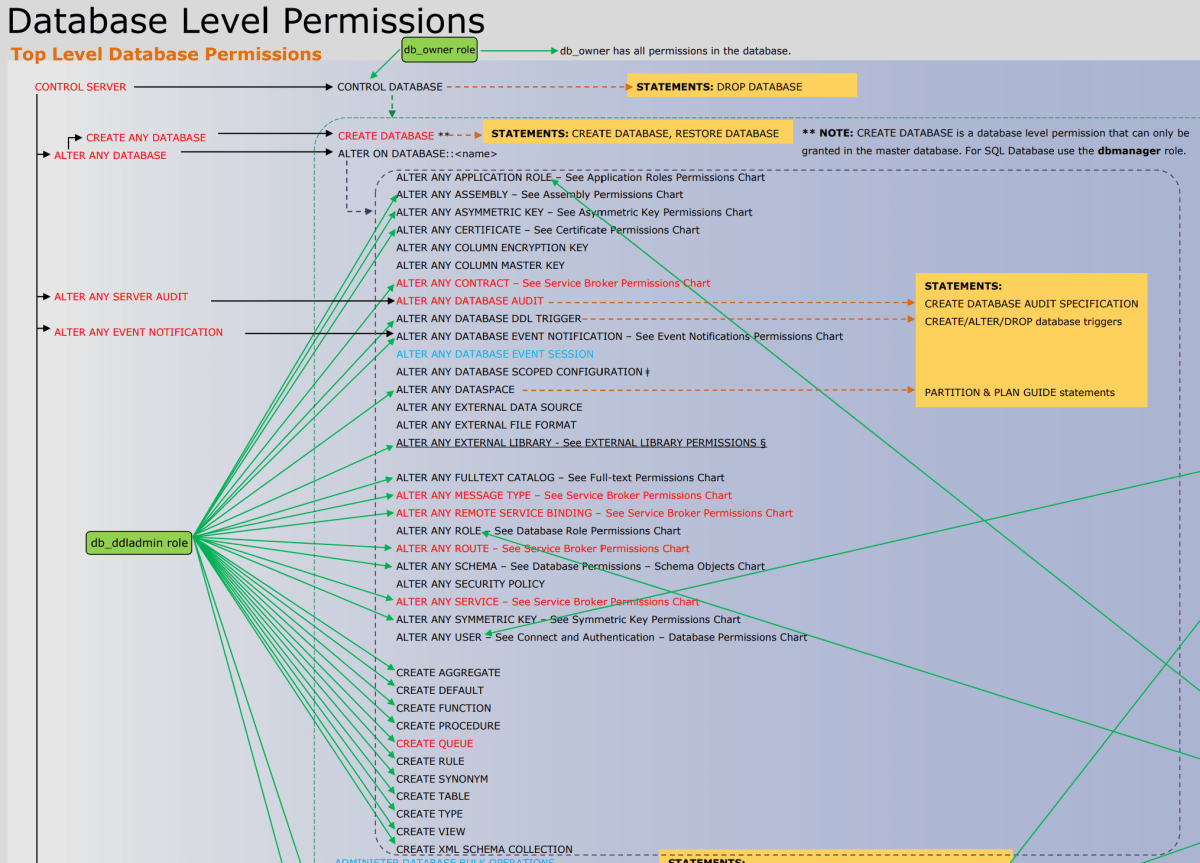

Diagram of permissions

The following image shows the permissions and their relationships to each other. Some of the higher level permissions (such as CONTROL SERVER) are listed many times. In this article, the poster is far too small to read. You can download the full-sized Database Engine Permissions Poster in PDF format.

For a graphic showing the relationships among the Database Engine principals and server and database objects, see Permissions Hierarchy (Database Engine).

Permissions vs. fixed server and fixed database roles

The permissions of the fixed server roles and fixed database roles are similar but not exactly the same as the granular permissions. For example, members of the sysadmin fixed server role have all permissions on the instance of SQL Server, as do logins with the CONTROL SERVER permission. But granting the CONTROL SERVER permission doesn't make a login a member of the sysadmin fixed server role, and adding a login to the sysadmin fixed server role doesn't explicitly grant the login the CONTROL SERVER permission. Sometimes a stored procedure will check permissions by checking the fixed role and not checking the granular permission. For example, detaching a database requires membership in the db_owner fixed database role. The equivalent CONTROL DATABASE permission isn't enough. These two systems operate in parallel but rarely interact with each other. Microsoft recommends using the newer, granular permission system instead of the fixed roles whenever possible.

Monitor permissions

The following views return security information.

The logins and user-defined server roles on a server can be examined by using the

sys.server_principalsview. This view isn't available in SQL Database.The users and user-defined roles in a database can be examined by using the

sys.database_principalsview.The permissions granted to logins and user-defined fixed server roles can be examined by using the

sys.server_permissionsview. This view isn't available in SQL Database.The permissions granted to users and user-defined fixed database roles can be examined by using the

sys.database_permissionsview.Database role membership can be examined by using the

sys.database_role_membersview.Server role membership can be examined by using the

sys.server_role_membersview. This view isn't available in SQL Database.For additional security related views, see Security Catalog Views (Transact-SQL).

Examples

The following statements return useful information about permissions.

A. List of database-permissions for each user

To return the explicit permissions granted or denied in a database (SQL Server and SQL Database), execute the following statement in the database.

SELECT

perms.state_desc AS State,

permission_name AS [Permission],

obj.name AS [on Object],

dp.name AS [to User Name]

FROM sys.database_permissions AS perms

JOIN sys.database_principals AS dp

ON perms.grantee_principal_id = dp.principal_id

JOIN sys.objects AS obj

ON perms.major_id = obj.object_id;

B. List server-role members

To return the members of the server roles (SQL Server only), execute the following statement.

SELECT roles.principal_id AS RolePrincipalID,

roles.name AS RolePrincipalName,

server_role_members.member_principal_id AS MemberPrincipalID,

members.name AS MemberPrincipalName

FROM sys.server_role_members AS server_role_members

INNER JOIN sys.server_principals AS roles

ON server_role_members.role_principal_id = roles.principal_id

LEFT JOIN sys.server_principals AS members

ON server_role_members.member_principal_id = members.principal_id;

C. List all database-principals that are members of a database-level role

To return the members of the database roles (SQL Server and SQL Database), execute the following statement in the database.

SELECT dRole.name AS [Database Role Name], dp.name AS [Members]

FROM sys.database_role_members AS dRo

JOIN sys.database_principals AS dp

ON dRo.member_principal_id = dp.principal_id

JOIN sys.database_principals AS dRole

ON dRo.role_principal_id = dRole.principal_id;

See also

- Security Center for SQL Server Database Engine and Azure SQL Database

- Security Functions (Transact-SQL)

- Security-Related Dynamic Management Views and Functions (Transact-SQL)

- Security Catalog Views (Transact-SQL)

- sys.fn_builtin_permissions (Transact-SQL)

- Determining Effective Database Engine Permissions