Text directionality

Writing systems differ in the scripts used, but also in their conventions for text directionality. Text directionality conventions can be combinations of left-to-right (LTR)/right-to-left (RTL) and top-to-bottom/bottom-to-top. For example:

- European languages using Latin script are typically written left-to-right, with lines from top-to-bottom.

- Chinese characters were historically written vertically, top-to-bottom starting on the right side; however, left-to-right, top-to-bottom is now also common.

- The traditional Mongolian script is typically written vertically, top-to-bottom, but unlike Chinese scripts, traditional Mongolian script is written starting on the left side.

Bidirectional text

Writing systems like Arabic and Hebrew use both LTR and RTL directionality depending on the characters. Basic letters flow from right-to-left, but digits especially when written using Latin numbers can be written left-to-right. Text that uses both directionalities is termed bidirectional (or bidi) text. While text might be displayed vertically, left-to-right and right-to-left, the Unicode standard specifies:

The order in which Unicode text is stored in the memory representation is called logical order. This order roughly corresponds to the order in which text is typed in via the keyboard; it also roughly corresponds to phonetic order.

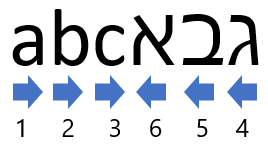

For bidi text, the order in which the user enters the text (the logical order) and the visual order (the order in which characters are presented to the user) are different in most cases:

Visual order:

Logical order:

Unicode publishes an algorithm describing how characters used in bidi text should be positioned. Each group of characters is rendered as a separate directional run in the correct direction, according to the algorithm.

Text directionality is supported in Unicode via the directional property on each character. Characters are categorized as strong, weak, neutral, or explicit formatting.

- Explicit formatting characters are Unicode characters that can be used to modify behavior. These include characters like the right-to-left mark (U+200F) which can be used in cases like positioning a punctuation mark correctly when it is between Arabic and Latin characters.

Strong characters

Strong characters have a consistent direction. They can be one of three types:

- left-to-right: for example, Latin alphabet, Han ideographs

- right-to-left: for example, Hebrew alphabet

- right-to-left Arabic: for example, Arabic alphabet and related punctuation

Sequences of one type of these characters causes the renderer to display the characters in a single group using the correct directionality.

Weak characters

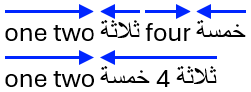

In RTL languages, numbers are displayed from left to right. They're categorized as having weak directionality and the algorithm treats them differently from characters and punctuation. Numerals will assume the directionality of the preceding character. Here's an example showing mixed English and Arabic text in a single LTR text block.

- one two ثلاثة four خمسة

- one two ثلاثة 4 خمسة

In the first example, [ثلاثة], [four], and [ خمسة] are seen as separate runs, first RTL, then LTR, finally RTL. In the second, numeral 4 is seen as part of a single RTL run: [ثلاثة 4 خمسة] and appears after the Arabic word ثلاثة (three) reading from right to left.

Neutral characters

Unlike strongly typed characters, spaces and punctuation characters can be used in either LTR or RTL languages and don't have LTR and RTL forms in Unicode. Hence, they're classified as Neutral.

The bidi algorithm renders neutral characters by looking at the characters surrounding them. A neutral character might fall between two characters of the same directionality (LTR or RTL) or between a strongly typed LTR character and a strongly typed RTL character.

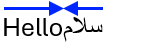

Neutral between characters of the same directionality

When a neutral character falls between two characters of the same directionality, it assumes the same directionality as the surrounding characters. The algorithm renders it as one run with the same directionality.

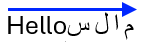

Neutral between characters of the opposite directionality

When a neutral character falls between two characters of the opposite directionality, it assumes the overall directionality of the whole paragraph or context. The following example shows the different scenarios of how the bidi algorithm renders text with neutral characters between characters of different directionalities: same directionality as the surrounding characters. Hence the bidi algorithm renders it as one run with the same directionality.

General context rules for the read order of text

The following are general context rules for the reading order and alignment of text:

- If the first strong character is LTR, reading order is left to right and text is left aligned.

- If the first strong character is RTL, reading order is right to left and text is right aligned.

- If only neutral characters are used, the reading order and the alignment follows the paragraph direction (can be left to right, or right to left) until the first strong character is reached.

Explicit formatting characters

You can use pairs of the following characters to specify the directionality of text within a longer text fragment.

- U+202A: LEFT-TO-RIGHT EMBEDDING (LRE)

- U+202B: RIGHT-TO-LEFT EMBEDDING (RLE)

- U+202D: LEFT-TO-RIGHT OVERRIDE (LRO)

- U+202E: RIGHT-TO-LEFT OVERRIDE (RLO)

- U+202C: POP DIRECTIONAL FORMATTING (PDF)

- U+2066: LEFT-TO-RIGHT ISOLATE (LRI)

- U+2067: RIGHT-TO-LEFT ISOLATE (RLI)

- U+2068: FIRST-STRONG ISOLATE (FSI)

- U+2069: POP DIRECTIONAL ISOLATE (PDI)

See Unicode’s description of how to use these directional formatting characters.

In addition, the following characters are categorized as strong in that they act as the respective right-to-left or left-to-right characters. They can be used to specify how the algorithm should treat the subsequent weak or neutral characters:

- U+061C: ARABIC LETTER MARK (ALM)

- U+200E: LEFT-TO-RIGHT MARK (LRM)

- U+200F: RIGHT-TO-LEFT MARK (RLM)

Let’s consider the previous example of:

one two ثلاثة 4 خمسة

If we insert a LRM before the number “4” and a RLM after the number “4”, we get:

one two ثلاثة 4 خمسة

We have indicated that “4” should be treated as a LTR run with a RTL either side of it.

Vertical text layout

In addition to the directional property for characters, Unicode also specifies a vertical orientation property. The vertical orientation property allows renderers to orient characters correctly when displayed in blocks of vertical lines. For example, Han ideographs, kana, and acronyms using Latin characters are displayed upright in vertical Japanese text. However, Latin characters that make up words and sentences can be rotated 90 degrees. In CSS, the effect can be achieved by using the text-orientation property in conjunction with the writing-mode property.

Implications for caret movement

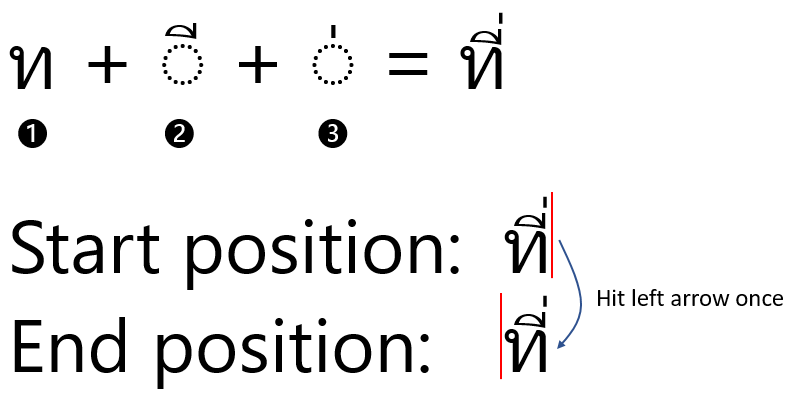

Text rendering and text directionality have implications for caret movement. Latin script only requires forward and backward movement of the caret. However, vertical text layout requires the caret to rotate by 90 degrees then an upwards and downwards movement of the caret. Some scripts require the caret to move over groups of characters. For example, in Thai if the caret is positioned after a base consonant, vowel, and tone mark, the cursor should skip back over the combined glyph when the user types the left arrow.

For bidirectional scripts, the direction of the caret movement might change depending on the direction of the text involved. For example, when using the arrow keys to move from right to left through Latin and then Hebrew text in the same sentence, the insertion point moves in a left-to-right manner through the Latin text and then continues at the rightmost character in the Hebrew text and progresses in a right-to-left manner.