Temporal table usage scenarios

Applies to:

SQL Server

System-versioned temporal tables are useful in scenarios that require tracking history of data changes. We recommend that you consider temporal tables in the following use cases, for major productivity benefits.

Data audit

You can use temporal system-versioning on tables that store critical information, to keep track of what changed and when, and to perform data forensics at any point in time.

Temporal tables allow you to plan for data audit scenarios in the early stages of the development cycle, or to add data auditing to existing applications or solutions when you need it.

The following diagram shows an Employee table with the data sample including current (marked with a blue color) and historical row versions (marked with a gray color).

The right-hand portion of the diagram visualizes row versions on a time axis, and the rows you select with different types of querying on temporal table, with or without the SYSTEM_TIME clause.

Enable system-versioning on a new table for data audit

If you identify information that needs data auditing, create database tables as system-versioned temporal tables. The following example illustrates a scenario with a table called Employee in hypothetical HR database:

CREATE TABLE Employee (

[EmployeeID] INT NOT NULL PRIMARY KEY CLUSTERED,

[Name] NVARCHAR(100) NOT NULL,

[Position] VARCHAR(100) NOT NULL,

[Department] VARCHAR(100) NOT NULL,

[Address] NVARCHAR(1024) NOT NULL,

[AnnualSalary] DECIMAL(10, 2) NOT NULL,

[ValidFrom] DATETIME2(2) GENERATED ALWAYS AS ROW START,

[ValidTo] DATETIME2(2) GENERATED ALWAYS AS ROW END,

PERIOD FOR SYSTEM_TIME(ValidFrom, ValidTo)

)

WITH (SYSTEM_VERSIONING = ON (HISTORY_TABLE = dbo.EmployeeHistory));

Various options to create temporal system-versioned table are described in Create a system-versioned temporal table.

Enable system-versioning on an existing table for data audit

If you need to perform data audit in existing databases, use ALTER TABLE to extend non-temporal tables to become system-versioned. In order to avoid breaking changes in your application, add period columns as HIDDEN, as explained in Create a system-versioned temporal table.

The following example illustrates enabling system-versioning on an existing Employee table in a hypothetical HR database. It enables system versioning in the Employee table in two steps. First, new period columns are added as HIDDEN. Then, it creates the default history table.

ALTER TABLE Employee ADD

ValidFrom DATETIME2(2) GENERATED ALWAYS AS ROW START HIDDEN

CONSTRAINT DF_ValidFrom DEFAULT DATEADD (SECOND, -1, SYSUTCDATETIME()),

ValidTo DATETIME2(2) GENERATED ALWAYS AS ROW END HIDDEN

CONSTRAINT DF_ValidTo DEFAULT '9999.12.31 23:59:59.99',

PERIOD FOR SYSTEM_TIME(ValidFrom, ValidTo);

ALTER TABLE Employee

SET (SYSTEM_VERSIONING = ON (HISTORY_TABLE = dbo.Employee_History));

Important

The precision of the datetime2 data type must be the same in the source table as it's in the system-versioned history table.

After you execute the previous script, all data changes will be collected transparently in the history table. In typical data audit scenario, you would query for all data changes that were applied to an individual row within a period of time of interest. The default history table is created with a clustered row-store B-tree, to efficiently address this use case.

Note

Documentation uses the term B-tree generally in reference to indexes. In rowstore indexes, the Database Engine implements a B+ tree. This does not apply to columnstore indexes or indexes on memory-optimized tables. For more information, see the SQL Server and Azure SQL index architecture and design guide.

Perform data analysis

After you enable system-versioning using either of the previous approaches, data auditing is just one query away. The following query searches for row versions for records in the Employee table, with EmployeeID = 1000 that were active at least for a portion of period between January 1, 2021 and January 1, 2022 (including the upper boundary):

SELECT * FROM Employee

FOR SYSTEM_TIME BETWEEN '2021-01-01 00:00:00.0000000'

AND '2022-01-01 00:00:00.0000000'

WHERE EmployeeID = 1000

ORDER BY ValidFrom;

Replace FOR SYSTEM_TIME BETWEEN...AND with FOR SYSTEM_TIME ALL to analyze the entire history of data changes for that particular employee:

SELECT * FROM Employee

FOR SYSTEM_TIME ALL

WHERE EmployeeID = 1000

ORDER BY ValidFrom;

To search for row versions that were active only within a period (and not outside of it), use CONTAINED IN. This query is efficient because it only queries the history table:

SELECT * FROM Employee

FOR SYSTEM_TIME CONTAINED IN (

'2021-01-01 00:00:00.0000000', '2022-01-01 00:00:00.0000000'

)

WHERE EmployeeID = 1000

ORDER BY ValidFrom;

Finally, in some audit scenarios, you might want to see how entire table looked like at any point in time in the past:

SELECT * FROM Employee

FOR SYSTEM_TIME AS OF '2021-01-01 00:00:00.0000000';

System-versioned temporal tables store values for period columns in the UTC time zone, but you might find it more convenient to work in your local time zone, both for filtering data and displaying results. The following code sample shows how to apply a filtering condition, which is specified in the local time zone and then converted to UTC using AT TIME ZONE, which was introduced in SQL Server 2016 (13.x):

/* Add offset of the local time zone to current time*/

DECLARE @asOf DATETIMEOFFSET = GETDATE() AT TIME ZONE 'Pacific Standard Time';

/* Convert AS OF filter to UTC*/

SET @asOf = DATEADD(HOUR, - 9, @asOf) AT TIME ZONE 'UTC';

SELECT EmployeeID,

[Name],

Position,

Department,

[Address],

[AnnualSalary],

ValidFrom AT TIME ZONE 'Pacific Standard Time' AS ValidFromPT,

ValidTo AT TIME ZONE 'Pacific Standard Time' AS ValidToPT

FROM Employee

FOR SYSTEM_TIME AS OF @asOf

WHERE EmployeeId = 1000;

Using AT TIME ZONE is helpful in all other scenarios where system-versioned tables are used.

Filtering conditions specified in temporal clauses with FOR SYSTEM_TIME are SARG-able. SARG stands for search argument, and SARG-able means that SQL Server can use the underlying clustered index to perform a seek instead of a scan operation. For more information, see SQL Server Index Architecture and Design Guide.

If you query the history table directly, make sure that your filtering condition is also SARG-able by specifying filters in form of <period column> { < | > | =, ... } date_condition AT TIME ZONE 'UTC'.

If you apply AT TIME ZONE to period columns, SQL Server performs a table or index scan, which can be very expensive. Avoid this type of condition in your queries:

<period column> AT TIME ZONE '<your time zone>' > {< | > | =, ...} date_condition.

For more information, see Query data in a system-versioned temporal table.

Point-in-time analysis (time travel)

Instead of focusing on changes to individual records, time travel scenarios show how entire data sets change over time. Sometimes time travel includes several related temporal tables, each changing at independent pace, for which you want to analyze:

- Trends for the important indicators in the historical and current data

- Exact snapshot of the entire data "as of" any point in time in the past (yesterday, a month ago, etc.)

- Differences in between two points in time of interest (a month ago vs. three months ago, for instance)

There are many real-world scenarios that require time travel analysis. To illustrate this usage scenario, let's look at OLTP with autogenerated history.

OLTP with autogenerated data history

In transaction processing systems, you can analyze how important metrics change over time. Ideally, analyzing history shouldn't compromise performance of the OLTP application where access to the latest state of data must occur with minimal latency and data locking. You can use system-versioned temporal tables to transparently keep the full history of changes for later analysis, separately from the current data, with a minimal impact on the main OLTP workload.

For high transactional processing workloads, we recommend that you use System-versioned temporal tables with memory-optimized tables, which allow you to store current data in-memory and full history of changes on disk in a cost effective way.

For the history table, we recommend that you use a clustered columnstore index for the following reasons:

Typical trend analysis benefits from query performance provided by a clustered columnstore index.

The data flush task with memory-optimized tables performs best under heavy OLTP workload when the history table has a clustered columnstore index.

A clustered columnstore index provides excellent compression, especially in scenarios where not all columns are changed at the same time.

Using temporal tables with in-memory OLTP reduces the need to keep the entire data set in-memory and enables you to easily distinguish between hot and cold data.

Examples of the real-world scenarios that fit well into this category are inventory management or currency trading, among others.

The following diagram shows simplified data model used for inventory management:

The following code example creates ProductInventory as an in-memory system-versioned temporal table, with a clustered columnstore index on the history table (which actually replaces the row-store index created by default):

Note

Make sure that your database allows creation of memory-optimized tables. See Creating a Memory-Optimized Table and a Natively Compiled Stored Procedure.

USE TemporalProductInventory;

GO

BEGIN

--If table is system-versioned, SYSTEM_VERSIONING must be set to OFF first

IF ((SELECT temporal_type

FROM SYS.TABLES

WHERE object_id = OBJECT_ID('dbo.ProductInventory', 'U')) = 2)

BEGIN

ALTER TABLE [dbo].[ProductInventory]

SET (SYSTEM_VERSIONING = OFF);

END

DROP TABLE IF EXISTS [dbo].[ProductInventory];

DROP TABLE IF EXISTS [dbo].[ProductInventoryHistory];

END

GO

CREATE TABLE [dbo].[ProductInventory] (

ProductId INT NOT NULL,

LocationID INT NOT NULL,

Quantity INT NOT NULL CHECK (Quantity >= 0),

ValidFrom DATETIME2 GENERATED ALWAYS AS ROW START NOT NULL,

ValidTo DATETIME2 GENERATED ALWAYS AS ROW END NOT NULL,

PERIOD FOR SYSTEM_TIME(ValidFrom, ValidTo),

--Primary key definition

CONSTRAINT PK_ProductInventory PRIMARY KEY NONCLUSTERED (

ProductId,

LocationId

)

)

WITH (

MEMORY_OPTIMIZED = ON,

SYSTEM_VERSIONING = ON (

HISTORY_TABLE = [dbo].[ProductInventoryHistory],

DATA_CONSISTENCY_CHECK = ON

)

);

CREATE CLUSTERED COLUMNSTORE INDEX IX_ProductInventoryHistory

ON [ProductInventoryHistory] WITH (DROP_EXISTING = ON);

For the previous model, this is how the procedure for maintaining inventory can look:

CREATE PROCEDURE [dbo].[spUpdateInventory]

@productId INT,

@locationId INT,

@quantityIncrement INT

WITH NATIVE_COMPILATION, SCHEMABINDING

AS

BEGIN ATOMIC

WITH (

TRANSACTION ISOLATION LEVEL = SNAPSHOT,

LANGUAGE = N'English'

)

UPDATE dbo.ProductInventory

SET Quantity = Quantity + @quantityIncrement

WHERE ProductId = @productId

AND LocationId = @locationId

-- If zero rows were updated then this is an insert

-- of the new product for a given location

IF @@rowcount = 0

BEGIN

IF @quantityIncrement < 0

SET @quantityIncrement = 0

INSERT INTO [dbo].[ProductInventory] (

[ProductId], [LocationID], [Quantity]

)

VALUES (@productId, @locationId, @quantityIncrement)

END

END;

The spUpdateInventory stored procedure either inserts a new product in the inventory or updates the product quantity for the particular location. The business logic is simple and focused on maintaining the latest state accurate all the time by incrementing / decrementing the Quantity field through table update, while system-versioned tables transparently add history dimension to the data, as depicted on the following diagram.

Now, querying of the latest state can be performed efficiently from the natively compiled module:

CREATE PROCEDURE [dbo].[spQueryInventoryLatestState]

WITH NATIVE_COMPILATION, SCHEMABINDING

AS

BEGIN ATOMIC

WITH (

TRANSACTION ISOLATION LEVEL = SNAPSHOT,

LANGUAGE = N'English'

)

SELECT ProductId, LocationID, Quantity, ValidFrom

FROM dbo.ProductInventory

ORDER BY ProductId, LocationId

END;

GO

EXEC [dbo].[spQueryInventoryLatestState];

Analyzing data changes over time becomes easy with the FOR SYSTEM_TIME ALL clause, as shown in the following example:

DROP VIEW IF EXISTS vw_GetProductInventoryHistory;

GO

CREATE VIEW vw_GetProductInventoryHistory

AS

SELECT ProductId,

LocationId,

Quantity,

ValidFrom,

ValidTo

FROM [dbo].[ProductInventory]

FOR SYSTEM_TIME ALL;

GO

SELECT * FROM vw_GetProductInventoryHistory

WHERE ProductId = 2;

The following diagram shows the data history for one product that can be easily rendered importing the previous view in Power Query, Power BI, or similar business intelligence tool:

Temporal tables can be used in this scenario to perform other types of time travel analysis, such as reconstructing the state of the inventory AS OF any point in time in the past or comparing snapshots that belong to different moments in time.

For this usage scenario, you can also extend the Product and Location tables to become temporal tables to enable later analysis of the history of changes of UnitPrice and NumberOfEmployee.

ALTER TABLE Product ADD

ValidFrom DATETIME2 GENERATED ALWAYS AS ROW START HIDDEN

CONSTRAINT DF_ValidFrom DEFAULT DATEADD (SECOND, -1, SYSUTCDATETIME()),

ValidTo DATETIME2 GENERATED ALWAYS AS ROW END HIDDEN

CONSTRAINT DF_ValidTo DEFAULT '9999.12.31 23:59:59.99',

PERIOD FOR SYSTEM_TIME(ValidFrom, ValidTo);

ALTER TABLE Product

SET (SYSTEM_VERSIONING = ON (HISTORY_TABLE = dbo.ProductHistory));

ALTER TABLE [Location] ADD

ValidFrom DATETIME2 GENERATED ALWAYS AS ROW START HIDDEN

CONSTRAINT DFValidFrom DEFAULT DATEADD (SECOND, -1, SYSUTCDATETIME()),

ValidTo DATETIME2 GENERATED ALWAYS AS ROW END HIDDEN

CONSTRAINT DFValidTo DEFAULT '9999.12.31 23:59:59.99',

PERIOD FOR SYSTEM_TIME(ValidFrom, ValidTo);

ALTER TABLE [Location]

SET (SYSTEM_VERSIONING = ON (HISTORY_TABLE = dbo.LocationHistory));

Since the data model now involves multiple temporal tables, the best practice for AS OF analysis is to create a view that extracts necessary data from the related tables and apply FOR SYSTEM_TIME AS OF to the view, as this greatly simplifies reconstructing the state of entire data model:

DROP VIEW IF EXISTS vw_ProductInventoryDetails;

GO

CREATE VIEW vw_ProductInventoryDetails

AS

SELECT PrInv.ProductId,

PrInv.LocationId,

P.ProductName,

L.LocationName,

PrInv.Quantity,

P.UnitPrice,

L.NumberOfEmployees,

P.ValidFrom AS ProductStartTime,

P.ValidTo AS ProductEndTime,

L.ValidFrom AS LocationStartTime,

L.ValidTo AS LocationEndTime,

PrInv.ValidFrom AS InventoryStartTime,

PrInv.ValidTo AS InventoryEndTime

FROM dbo.ProductInventory AS PrInv

INNER JOIN dbo.Product AS P

ON PrInv.ProductId = P.ProductID

INNER JOIN dbo.Location AS L

ON PrInv.LocationId = L.LocationID;

GO

SELECT * FROM vw_ProductInventoryDetails

FOR SYSTEM_TIME AS OF '2022-01-01';

The following screenshot shows the execution plan generated for the SELECT query. This illustrates that the Database Engine handles all the complexity when dealing with temporal relations:

Use the following code to compare state of product inventory between two points in time (a day ago and a month ago):

DECLARE @dayAgo DATETIME2 = DATEADD (DAY, -1, SYSUTCDATETIME());

DECLARE @monthAgo DATETIME2 = DATEADD (MONTH, -1, SYSUTCDATETIME());

SELECT inventoryDayAgo.ProductId,

inventoryDayAgo.ProductName,

inventoryDayAgo.LocationName,

inventoryDayAgo.Quantity AS QuantityDayAgo,

inventoryMonthAgo.Quantity AS QuantityMonthAgo,

inventoryDayAgo.UnitPrice AS UnitPriceDayAgo,

inventoryMonthAgo.UnitPrice AS UnitPriceMonthAgo

FROM vw_ProductInventoryDetails

FOR SYSTEM_TIME AS OF @dayAgo AS inventoryDayAgo

INNER JOIN vw_ProductInventoryDetails

FOR SYSTEM_TIME AS OF @monthAgo AS inventoryMonthAgo

ON inventoryDayAgo.ProductId = inventoryMonthAgo.ProductId

AND inventoryDayAgo.LocationId = inventoryMonthAgo.LocationID;

Anomaly detection

Anomaly detection (or outlier detection) is the identification of items that don't conform to an expected pattern or other items in a dataset. You can use system-versioned temporal tables to detect anomalies that occur periodically or irregularly as you can utilize temporal querying to quickly locate specific patterns. What anomaly is depends on type of data you collect and your business logic.

The following example shows simplified logic for detecting "spikes" in sales numbers. Let's assume that you work with a temporal table that collects history of the products purchased:

CREATE TABLE [dbo].[Product] (

[ProdID] [int] NOT NULL PRIMARY KEY CLUSTERED,

[ProductName] [varchar](100) NOT NULL,

[DailySales] INT NOT NULL,

[ValidFrom] [datetime2] GENERATED ALWAYS AS ROW START NOT NULL,

[ValidTo] [datetime2] GENERATED ALWAYS AS ROW END NOT NULL,

PERIOD FOR SYSTEM_TIME([ValidFrom], [ValidTo])

)

WITH (

SYSTEM_VERSIONING = ON (

HISTORY_TABLE = [dbo].[ProductHistory],

DATA_CONSISTENCY_CHECK = ON

)

);

The following diagram shows the purchases over time:

Assuming that during the regular days the number of purchased products has a small variance, the following query identifies singleton outliers: samples which difference compared to their immediate neighbors is significant (2x), while surrounding samples don't differ significantly (less than 20%):

WITH CTE (

ProdId,

PrevValue,

CurrentValue,

NextValue,

ValidFrom,

ValidTo

)

AS (

SELECT ProdId,

LAG(DailySales, 1, 1) OVER (PARTITION BY ProdId ORDER BY ValidFrom) AS PrevValue,

DailySales,

LEAD(DailySales, 1, 1) OVER (PARTITION BY ProdId ORDER BY ValidFrom) AS NextValue,

ValidFrom,

ValidTo

FROM Product

FOR SYSTEM_TIME ALL

)

SELECT ProdId,

PrevValue,

CurrentValue,

NextValue,

ValidFrom,

ValidTo,

ABS(PrevValue - NextValue) / convert(FLOAT, (

CASE

WHEN NextValue > PrevValue THEN PrevValue

ELSE NextValue

END)) AS PrevToNextDiff,

ABS(CurrentValue - PrevValue) / convert(FLOAT, (

CASE

WHEN CurrentValue > PrevValue THEN PrevValue

ELSE CurrentValue

END)) AS CurrentToPrevDiff,

ABS(CurrentValue - NextValue) / convert(FLOAT, (

CASE

WHEN CurrentValue > NextValue THEN NextValue

ELSE CurrentValue

END)) AS CurrentToNextDiff

FROM CTE

WHERE ABS(PrevValue - NextValue) / (

CASE

WHEN NextValue > PrevValue THEN PrevValue

ELSE NextValue

END) < 0.2

AND ABS(CurrentValue - PrevValue) / (

CASE

WHEN CurrentValue > PrevValue THEN PrevValue

ELSE CurrentValue

END) > 2

AND ABS(CurrentValue - NextValue) / (

CASE

WHEN CurrentValue > NextValue THEN NextValue

ELSE CurrentValue

END) > 2;

Note

This example is intentionally simplified. In the production scenarios, you would likely use advanced statistical methods to identify samples which don't follow the common pattern.

Slowly changing dimensions

Dimensions in data warehousing typically contain relatively static data about entities such as geographical locations, customers, or products. However, some scenarios require you to track data changes in dimension tables as well. Given that modifications in dimensions happen much less frequently, in unpredictable manner and outside of the regular update schedule that applies to fact tables, these types of dimension tables are called slowly changing dimensions (SCD).

There are several categories of slowly changing dimensions based on how history of changes is preserved:

| Dimension type | Details |

|---|---|

| Type 0 | History isn't preserved. Dimension attributes reflect original values. |

| Type 1 | Dimension attributes reflect latest values (previous values are overwritten) |

| Type 2 | Every version of dimension member represented with separate row in the table usually with columns that represent period of validity |

| Type 3 | Keeping limited history for selected attributes using extra columns in the same row |

| Type 4 | Keeping history in the separate table while original dimension table keeps latest (current) dimension member versions |

When you choose an SCD strategy, it's the responsibility of the ETL layer (Extract-Transform-Load) to keep dimension tables accurate, which usually requires more complex code and extra maintenance.

System-versioned temporal tables can be used to dramatically lower the complexity of your code as history of data is automatically preserved. Given its implementation using two tables, temporal tables are closest to Type 4 SCD. However, since temporal queries allow you to reference the current table only, you can also consider temporal tables in environments where you plan to use Type 2 SCD.

In order to convert your regular dimension to SCD, you can create a new one or alter an existing one to become a system-versioned temporal table. If your existing dimension table contains historical data, create separate table and move historical data there and keep current (actual) dimension versions in your original dimension table. Then use ALTER TABLE syntax to convert your dimension table to a system-versioned temporal table with a predefined history table.

The following example illustrates the process and assumes that the DimLocation dimension table already has ValidFrom and ValidTo as datetime2 non-nullable columns, which are populated by the ETL process:

/* Move "closed" row versions into newly created history table*/

SELECT * INTO DimLocationHistory

FROM DimLocation

WHERE ValidTo < '9999-12-31 23:59:59.99';

GO

/* Create clustered columnstore index which is a very good choice in DW scenarios*/

CREATE CLUSTERED COLUMNSTORE INDEX IX_DimLocationHistory ON DimLocationHistory;

/* Delete previous versions from DimLocation which will become current table in temporal-system-versioning configuration*/

DELETE FROM DimLocation

WHERE ValidTo < '9999-12-31 23:59:59.99';

/* Add period definition*/

ALTER TABLE DimLocation

ADD PERIOD FOR SYSTEM_TIME(ValidFrom, ValidTo);

/* Enable system-versioning and bind history table to the DimLocation*/

ALTER TABLE DimLocation

SET (SYSTEM_VERSIONING = ON (HISTORY_TABLE = dbo.DimLocationHistory));

No extra code is required to maintain SCD during the data warehouse loading process once you created it.

The following illustration shows how you can use temporal tables in a simple scenario involving two SCDs (DimLocation and DimProduct) and one fact table.

In order to use previous SCDs in reports, you need to effectively adjust querying. For example, you might want to calculate the total sales amount and the average number of sold products per capita for the last six months. Both metrics require the correlation of data from the fact table and dimensions that might have changed their attributes important for the analysis (DimLocation.NumOfCustomers, DimProduct.UnitPrice). The following query properly calculates the required metrics:

DECLARE @now DATETIME2 = SYSUTCDATETIME();

DECLARE @sixMonthsAgo DATETIME2;

SET @sixMonthsAgo = DATEADD(month, - 12, SYSUTCDATETIME());

SELECT DimProduct_History.ProductId,

DimLocation_History.LocationId,

SUM(F.Quantity * DimProduct_History.UnitPrice) AS TotalAmount,

AVG(F.Quantity / DimLocation_History.NumOfCustomers) AS AverageProductsPerCapita

FROM FactProductSales F

/* find corresponding record in SCD history in last 6 months, based on matching fact */

INNER JOIN DimLocation

FOR SYSTEM_TIME BETWEEN @sixMonthsAgo AND @now AS DimLocation_History

ON DimLocation_History.LocationId = F.LocationId

AND F.FactDate BETWEEN DimLocation_History.ValidFrom AND DimLocation_History.ValidTo

/* find corresponding record in SCD history in last 6 months, based on matching fact */

INNER JOIN DimProduct

FOR SYSTEM_TIME BETWEEN @sixMonthsAgo AND @now AS DimProduct_History

ON DimProduct_History.ProductId = F.ProductId

AND F.FactDate BETWEEN DimProduct_History.ValidFrom AND DimProduct_History.ValidTo

WHERE F.FactDate BETWEEN @sixMonthsAgo AND @now

GROUP BY DimProduct_History.ProductId, DimLocation_History.LocationId;

Considerations

Using system-versioned temporal tables for SCD is acceptable if period of validity calculated based on database transaction time is fine with your business logic. If you load data with significant delay, transaction time might not be acceptable.

By default, system-versioned temporal tables don't allow changing historical data after loading (you can modify history after you set SYSTEM_VERSIONING to OFF). This might be a limitation in cases where changing historical data happens regularly.

Temporal system-versioned tables generate row version on any column change. If you want to suppress new versions on certain column change, you need to incorporate that limitation in the ETL logic.

If you expect a significant number of historical rows in SCD tables, consider using a clustered columnstore index as the main storage option for history table. Using a columnstore index reduces the history table footprint and speeds up your analytical queries.

Repair row-level data corruption

You can rely on historical data in system-versioned temporal tables to quickly repair individual rows to any of the previously captured states. This property of temporal tables is useful when you're able to locate affected rows, and/or when you know the time of undesired data change. This knowledge lets you perform repair efficiently without dealing with backups.

This approach has several advantages:

You're able to control the scope of the repair precisely. Records that aren't affected need to stay at the latest state, which is often a critical requirement.

Operation is efficient and the database stays online for all workloads using the data.

The repair operation itself is versioned. You have audit trail for repair operation itself, so you can analyze what happened later if necessary.

Repair action can be automated with relative ease. The next code example shows a stored procedure that performs data repair for the table Employee used in a data audit scenario.

DROP PROCEDURE IF EXISTS sp_RepairEmployeeRecord;

GO

CREATE PROCEDURE sp_RepairEmployeeRecord

@EmployeeID INT,

@versionNumber INT = 1

AS

WITH History

AS (

/* Order historical rows by their age in DESC order*/

SELECT

ROW_NUMBER() OVER (PARTITION BY EmployeeID

ORDER BY [ValidTo] DESC) AS RN,

*

FROM Employee FOR SYSTEM_TIME ALL

WHERE YEAR(ValidTo) < 9999 AND Employee.EmployeeID = @EmployeeID

)

/* Update current row by using N-th row version from history (default is 1 - i.e. last version) */

UPDATE Employee

SET [Position] = H.[Position],

[Department] = H.Department,

[Address] = H.[Address],

AnnualSalary = H.AnnualSalary

FROM Employee E

INNER JOIN History H ON E.EmployeeID = H.EmployeeID AND RN = @versionNumber

WHERE E.EmployeeID = @EmployeeID;

This stored procedure takes @EmployeeID and @versionNumber as input parameters. This procedure by default restores row state to the last version from the history (@versionNumber = 1).

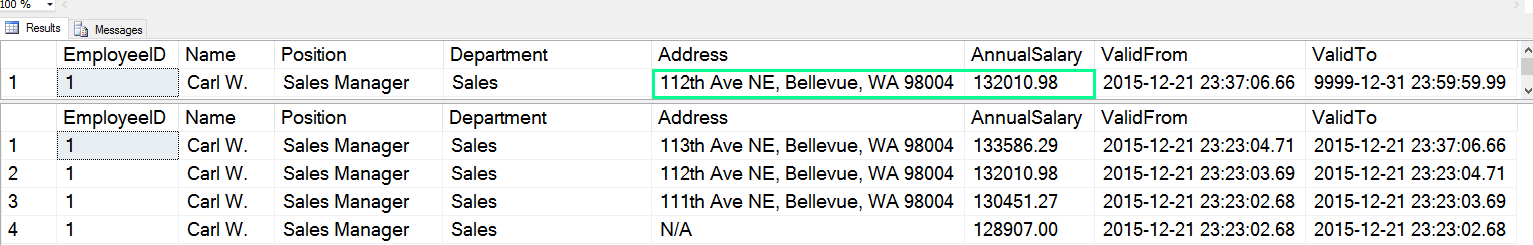

The following picture shows state of the row before and after the procedure invocation. Red rectangle marks current row version that is incorrect, while green rectangle marks correct version from the history.

EXEC sp_RepairEmployeeRecord @EmployeeID = 1, @versionNumber = 1;

This repair stored procedure can be defined to accept an exact timestamp instead of row version. It restores the row to any version that was active for the point in time provided (that is, AS OF point in time).

DROP PROCEDURE IF EXISTS sp_RepairEmployeeRecordAsOf;

GO

CREATE PROCEDURE sp_RepairEmployeeRecordAsOf

@EmployeeID INT,

@asOf DATETIME2

AS

/* Update current row to the state that was actual AS OF provided date*/

UPDATE Employee

SET [Position] = History.[Position],

[Department] = History.Department,

[Address] = History.[Address],

AnnualSalary = History.AnnualSalary

FROM Employee AS E

INNER JOIN Employee FOR SYSTEM_TIME AS OF @asOf AS History

ON E.EmployeeID = History.EmployeeID

WHERE E.EmployeeID = @EmployeeID;

For the same data sample, the following picture illustrates a repair scenario with a time condition. Highlighted are the @asOf parameter, selected row in the history that was actual at the provided point in time, and new row version in the current table after repair operation:

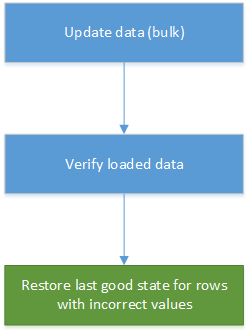

Data correction can become part of automated data loading in data warehousing and reporting systems. If a newly updated value isn't correct, then in many scenarios, restoring the previous version from history is good enough mitigation. The following diagram shows how this process can be automated:

Related content

- Temporal tables

- Get started with system-versioned temporal tables

- Temporal table system consistency checks

- Partition with temporal tables

- Temporal table considerations and limitations

- Temporal table security

- System-versioned temporal tables with memory-optimized tables

- Temporal table metadata views and functions